|

Pentagon:

Special Ops Killing of Pregnant Afghan Women Was

“Appropriate” Use of Force

By Jeremy

Scahill

June 02,

2016 "Information

Clearing House"

-

The Intercept

-

In internal Defense Department

investigation into one of the most notorious night

raids conducted by special operations forces in

Afghanistan — in which seven civilians were killed,

including two pregnant women — determined that all

the U.S. soldiers involved had followed the rules of

engagement. As a result, the soldiers faced no

disciplinary measures, according to hundreds of

pages of Defense Department

documents obtained by The Intercept

through the Freedom of Information Act. In

the aftermath of the raid, Adm. William McRaven, at

the time the commander of the elite Joint Special

Operations Command, took responsibility for the

operation. The documents made no unredacted mention

of JSOC.

Although

two children were shot during the raid and multiple

witnesses and Afghan investigators alleged that U.S.

soldiers dug bullets out of the body of at least one

of the dead pregnant women, Defense Department

investigators concluded that “the amount of force

utilized was necessary, proportional and applied at

appropriate time.” The investigation did

acknowledge that “tactical mistakes” were made.

The Defense

Department’s conclusions bear a resemblance to U.S.

Central Command’s findings in the aftermath of the

horrifying attack on a Médecins Sans Frontières

hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, last October in

which 42 patients and medical workers were killed in

a sustained barrage of strikes by an AC-130. The

Pentagon has announced that no criminal charges will

be brought against any members of the military for

the Kunduz strike. CENTCOM’s Kunduz

investigation concluded that “the incident resulted

from a combination of unintentional human errors,

process errors, and equipment failures.” CENTCOM

denied the attack constituted a war crime, a claim

challenged by international law experts and MSF.

The

February 2010 night raid, which took place in a

village near Gardez in Paktia province, was

described by the U.S. military at the time as a

heroic attack against Taliban militants. A press

release published by NATO in Afghanistan soon after

the raid asserted that a joint Afghan-international

operation had made a “gruesome discovery.” According

to NATO, the force entered a compound near the

village of Khataba after intelligence had

“confirmed” it to be the site of “militant

activity.” As the team approached, they were

“engaged” in a “fire fight” by “several insurgents.”

The Americans killed the insurgents and were

securing the area when they made their discovery:

three women who had been “bound and gagged” and then

executed inside the compound. The U.S. force, the

press release alleged, found the women “hidden in an

adjacent room.” The story was picked up and spread

throughout the media. A “senior U.S. military

official” told CNN that the bodies had “the earmarks

of a traditional honor killing.”

But the raid

quickly gained international infamy after survivors

and local Afghan investigators began offering a

completely different narrative of the deadly events

that night to a British reporter, Jerome Starkey,

who began a serious investigation of the Gardez

killings. When I visited Starkey in Kabul, he told

me that at first he saw no reason to discount the

official story. “I thought it was worth

investigating because if that press release was true

— a mass honor killing, three women killed by

Taliban who were then killed by Special Forces —

that in itself would have made an extraordinary and

intriguing story.” But when he traveled to Gardez

and began assembling witnesses to meet him in the

area, he immediately realized NATO’s story was

likely false. Starkey’s reporting, which first

uncovered the horrifying details of what happened

that night, forced NATO and the U.S. military to

abandon the honor killings cover story. A

half-hearted official investigation ensued.

Witnesses

and survivors described an unprovoked assault on the

family compound of Mohammed Daoud Sharabuddin, a

police officer who had just received an important

promotion. Daoud and his family had gathered to

celebrate the naming of a newborn son, a ritual that

takes place on the sixth day of a child’s life.

Unlike the predominantly Pashtun Taliban, the

Sharabuddin family were ethnic Tajiks, and their

main language was Dari. Many of the men in the

family were clean-shaven or wore only mustaches, and

they had long opposed the Taliban. Daoud, the police

commander, had gone through dozens of U.S. training

programs, and his home was filled with photos of

himself with American soldiers. Another family

member was a prosecutor for the U.S.-backed local

government, and a third was the vice chancellor at

the local university.

At about

3:30 a.m., when the family heard noises outside

their compound, Daoud and his 15-year-old son

Sediqullah, fearing a Taliban attack, went outside

to investigate. Both were immediately hit with

sniper fire.

“All the

children were shouting, ‘Daoud is shot! Daoud is

shot!’” Daoud’s brother-in-law Tahir recalled when I

visited the family compound in 2010. Daoud’s eldest

son was behind his father and younger brother when

they were hit. “When my father went down, I

screamed,” he told me. “Everybody — my uncles, the

women, everybody came out of the home and ran to the

corridors of the house. I sprinted to them and

warned them not to come out as there were Americans

attacking and they would kill them.”

Within a

matter of minutes, a family celebration had become a

massacre. Seven people died, including three women

and two people who later succumbed to their

injuries. Two of the women had been pregnant.

Sixteen children lost their mothers.

The

Americans were still present when survivors prepared

burial shrouds for those who had died. The Afghan

custom involves binding the feet and head. A scarf

secured around the bottom of the chin is meant to

keep the mouth of the deceased from hanging open.

They managed to do this before the Americans began

handcuffing them and dividing the surviving men and

women into separate areas. Several of the male

family members told me that it was around this time

that they witnessed a horrifying scene: U.S.

soldiers digging the bullets out of the women’s

bodies. “They were putting knives into their

injuries to take out the bullets,” Sabir told me. I

asked him bluntly, “You saw the Americans digging

the bullets out of the women’s bodies?” Without

hesitation, he said, “Yes.” Tahir told me he saw the

Americans with knives standing over the bodies.

“They were taking out the bullets from their bodies

to remove the proof of their crime.”

Months after

the February 2010 night raid, Jeremy Scahill

interviewed survivors. A brief clip from

Dirty Wars.

The U.S.

military’s internal investigation into the raid,

which was described in detail in the documents

obtained by The Intercept, was ordered by

Gen. Stanley McChrystal, the former commander of the

Joint Special Operations Command, who at the time of

the raid was the commander of all international

forces in Afghanistan. The lead investigator, whose

identity was redacted, noted at the beginning of the

report that he did not visit the scene of the raid,

saying that the risks of “re-awakening emotional and

political turmoil” would not have been “worth the

cost.” Instead, family members of the victims were

asked to travel to a U.S. base to be interviewed.

The

documents’ redactions and omissions are perhaps more

interesting than the conclusions of the

investigation. U.S. Central Command released 535

pages, including more than 100 photographs taken at

the scene, but withheld nearly 400 additional pages,

stating that they are exempt from FOIA for national

security reasons. Photographs of bodies and wounds

were redacted. The documents include NATO press

releases and talking points claiming that the

victims of the U.S. attack were Taliban militants

and offering the standard assurances that “Coalition

Forces take every precaution to ensure non-combatant

civilians are protected from possible hostilities

during the course of every operation.” An

error-laden “questions and answers” document stated

that during the operation, “two militants [were]

killed and one wounded,” and “one women and two

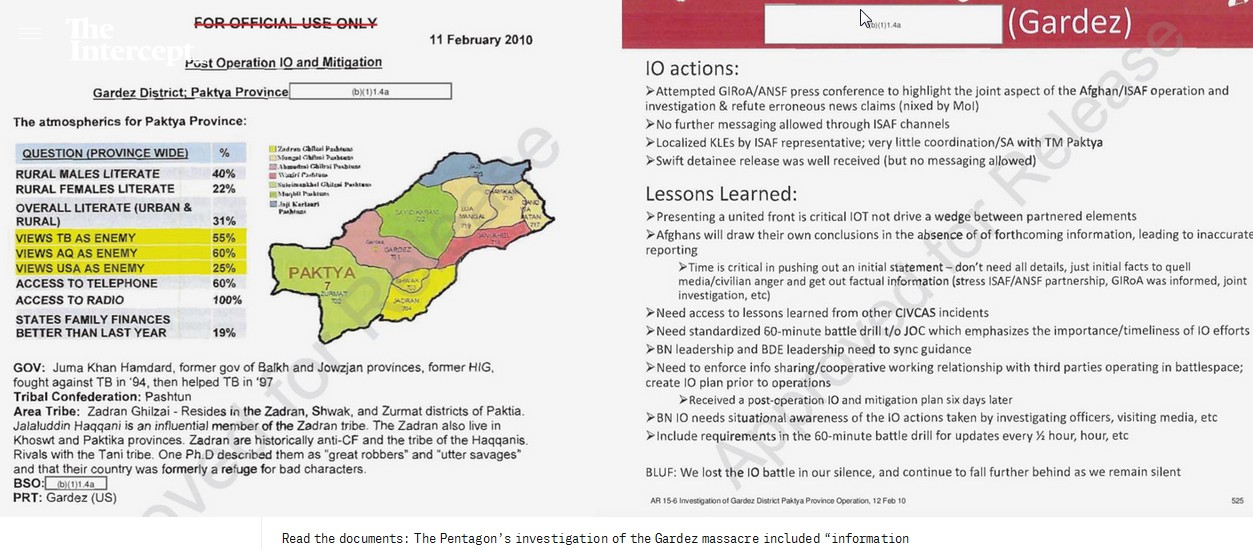

children were protected.” A list of talking points

titled “Post Operation IO and Mitigation”

characterized the “Area Tribe” in the following

terms: “One Ph.D described them as ‘great robbers’

and ‘utter savages’ and that their country was

formerly a refuge for bad characters.”

While the

investigation asserted that the soldiers did not dig

any bullets out of the bodies of the dead, the

sections of the investigation addressing this

allegation were almost entirely redacted. The

investigation found that the survivors interviewed

in the raid’s aftermath, referred to as “detainees,”

provided credible testimony. The report also noted

“consistency in all eight detainees’ statements that

would be impossible to pre-plan without prior

knowledge of specifics of the operation,” adding

that “the detainee reports corroborate that the

women died when they tried to stop Zahir [one of the

men killed] from exiting the building.”

Despite

this assessment of the credibility of the survivors’

testimony, the Pentagon investigation dismissed

outright the statements from multiple witnesses,

including the husband of one of the dead women, that

the Americans dug bullets from the women’s bodies.

“This investigation found no attempt to hide or

cover up the circumstances of the local national

women’s deaths,” the executive summary of the

investigation concluded. The investigators were

instructed by the main U.S. command at Bagram to

determine: “Did anyone alter, clean or otherwise

tamper with the scene in any way following the

operation, and if so, why?” The answer to that

question was completely redacted.

Initial

instructions given to Defense Department public

relations staff on how to discuss the Gardez

raid.

The

investigation did note, however, that the Afghan

investigation conducted immediately after the raid

“reports that an American bullet was found in the

body of one of the dead women, but it does not say

how that bullet was found or who removed it from the

woman.” Citing statements from the members of the

strike force that conducted the raid, the

investigators asserted, “There is no evidence to

support that bullets were removed from the bodies by

anyone associated with U.S. forces.”

The initial

press release on the raid contained erroneous

information about the women being bound and gagged,

according to the investigation, because “the ground

force was confused by the unfamiliar sight of the

women prepared so quickly for burial and firmly

believed that they did not kill the three women.”

The investigation concluded that the “assumption”

that the women “had been killed by Afghans and

placed on the scene” was an “honest assessment” and

the result of a “lack of cultural awareness,” not

“an attempt to mislead higher headquarters.”

According

to the instructions provided to investigators, the

U.S. forces claimed the women had been killed as

many as two days before the raid occurred, but the

report observed that their “remains were collocated

with EKIA,” enemies killed in action, and photos

taken in the immediate aftermath showed the women

with wounds indicating they had been killed during

the raid. “Was this an attempt to deceive?” That

question was not answered in the documents provided

by the Pentagon, at least not in an unredacted

format.

The report

also noted a curious contradiction. One of the men

killed by American forces had been prepared for

burial just as the dead women were — with a cloth

wrap tied around his head so his jaw would remain

closed. Yet when the U.S. forces first reported on

the raid, they described only the women as having

their heads bound and suggested their deaths were

the result of a “cultural custom.”

The cause

of death listed for the men was gunshot wounds to

the chest. For the three women, the cause of death

was “wounds.” The most credible theory, according to

the final report, was that the women were killed in

a “shoot through” once the raid had begun, and that

their deaths were unintentional — and unknown to the

shooters.

“It is

undeniable that five innocent people were killed and

two innocent men were wounded in the conduct of this

operation,” the report stated. “To simply call this

‘regrettable’ would be callous; it is much more than

that. However, the unique chain of events that led

to their deaths is explicable.”

According

to the report, the university official who was at

the party inside the compound called the police

headquarters in Paktia as the raid was beginning

because he believed the house was coming under

attack from the Taliban. All the witnesses

interviewed stated that Mohammed Daoud, the Afghan

police commander, left the party and entered the

courtyard, believing he was confronting a Taliban

attack. Still, the investigation concluded that the

U.S. forces were justified in shooting him, as well

as his cousin Mohammed Saranwal Zahir, the local

prosecutor. The investigators found that the men had

showed “hostile intent” because they were armed with

rifles.

In the end,

the investigation determined that American forces

had followed the rules of engagement and standard

operating procedures during the raid, concluding

only that there were “tactical mistakes made.” The

investigation recommended that the coalition forces

“make an appropriate condolence payment to the

family as a sign of good faith in our sincerity at

the seriousness of the incident.”

Because of

excessive redactions, these documents fail to answer

many questions. While the report referenced “Special

Forces,” the specific unit was redacted. The report

also seemed to indicate that the strike force came

from a base in another province, rather than the

local base in Paktia, yet offered no explanation.

The letter accompanying the documents provided to

The Intercept stated that some documents

could not be released because they would expose

“inter-agency and intra-agency memorandum.” What

other agencies were involved in this raid and

subsequent management of the fallout and

investigation? Who provided the Americans with the

intelligence that led to the raid, which claimed

that a Taliban facilitator was present? No

explanation was given for why the documents, which

were requested from SOCOM, the parent command of

JSOC, under the Freedom of Information Act in March

2011, were only now released, after being reviewed

by another — unnamed — agency.

The report

noted that “there are considerable questions about

the cause of the females’ deaths and males’

injuries” as well as “multiple inconsistencies

between what was observed and what has since been

reported by local nationals.” If the women were

killed by U.S. forces, even in a “shoot through,”

what happened to the bullets? The report stated that

the throat of one of the women had been slit with a

knife and that another dead body contained knife

marks on the chest. Where did these lacerations come

from? One investigator observed a blood splatter

pattern that “appeared to be more consistent with

blunt force trauma” and suggested “someone had

possibly slipped on the ice and split open his or

her head on the hard concrete.” If that is truly

what the splatter indicated, then which person

received those injuries? If the investigators

determined the surviving witnesses of the raid were

convincing and credible, why then was their

testimony about Americans digging bullets out of the

women’s dead bodies discarded?

Mohammed

Sabir was one of the men singled out for further

interrogation after the raid. With his clothes still

caked with the blood of his loved ones, Sabir and

seven other men were hooded and shackled. “They tied

our hands and blindfolded us,” he recalled. “Two

people grabbed us and pushed us, one by one, into

the helicopter.” They were flown to a different

Afghan province, Paktika, where the Americans held

them for days. “My senses weren’t working at all,”

he recalled. “I couldn’t cry, I was numb. I didn’t

eat for three days and nights. They didn’t give us

water to wash the blood away.” The Americans ran

biometric tests on the men, photographed their

irises, and took their fingerprints. Sabir described

to me how teams of interrogators, including both

Americans and Afghans, questioned him about his

family’s connections to the Taliban. Sabir told them

that his family was against the Taliban, had fought

the Taliban, and that some relatives had been

kidnapped by the Taliban.

“The

interrogators had short beards and didn’t wear

uniforms. They had big muscles and would fly into

sudden rages,” Sabir recalled, adding that they

shook him violently at times. “We told them

truthfully that there were not Taliban in our home.”

One of the Americans, he said, told him they “had

intelligence that a suicide bomber had hidden in

your house and that he was planning an operation.”

Sabir told them, “If we would have had a suicide

bomber at home, then would we be playing music in

our house? Almost all guests were government

employees.” By the time Mohammed Sabir returned home

after being held in American custody, he had missed

the burial of his wife and other family members.

The Pentagon

investigation stands in stark contrast to an

independent investigation conducted by a United

Nations team, which determined that the survivors of

the raid “suffered from cruel, inhuman and degrading

treatment by being physically assaulted by U.S. and

Afghan forces, restrained and forced to stand bare

feet for several hours outside in the cold.” The

U.N. investigation added that witnesses alleged

“that U.S. and Afghan forces refused to provide

adequate and timely medical support to two people

who sustained serious bullet injuries, resulting in

their death hours later.” The Pentagon investigation

did note that three of the survivors detained stated

they had been “tortured by Special Forces,” but that

allegation was buried below statements attributed to

other survivors who said being held by the American

forces “felt like home not like prisoner” and they

were treated “very well.”

In the end,

the commander of the Joint Special Operations

Command, Vice Adm. William McRaven, visited the

compound in Gardez accompanied by a phalanx of

Afghan and U.S. soldiers. He made an offer to the

family to sacrifice a sheep, which his force had

brought with them on a truck, to ask forgiveness.

Months later,

when I sat with the family elder, Hajji Sharabuddin,

at his home, his anger seemed only to have hardened.

“I don’t accept their apology. I would not trade my

sons for the whole kingdom of the United States,” he

told me, holding up a picture of his sons.

“Initially, we were thinking that Americans were the

friends of Afghans, but now we think that Americans

themselves are terrorists. Americans are our enemy.

They bring terror and destruction. Americans not

only destroyed my house, they destroyed my family.

The Americans unleashed the Special Forces on us.

These Special Forces, with the long beards, did

cruel, criminal things.”

“We call them

the American Taliban,” added Mohammed Tahir, the

father of Gulalai, one of the slain women.

The

internal investigation ordered by Gen. McChrystal

into the Gardez raid is an incomplete accounting of

this horrifying incident. It is also based on the

word of the force that carried out the killings,

whose personnel could have faced serious charges

under the Uniform Code of Military Justice if

investigators had taken seriously the survivors’

allegations.

Portions of this article were adapted from Scahill’s

2014 book, Dirty Wars. |