|

Some

Real Costs of the Trans-Pacific Partnership: Nearly

Half a Million Jobs Lost in the US Alone

By Jomo Kwame Sundaram

March 01, 2016 "Information

Clearing House"

- "NC"

- The Trans-Pacifc Partnership (TPP) Agreement,

recently agreed to by twelve Pacifc Rim countries

led by the United States,1 promises to

ease many restrictions on cross-border transactions

and harmonize regulations. Proponents of the

agreement have claimed significant economic

benefits, citing modest overall net GDP gains,

ranging from half of one percent in the United

States to 13 percent in Vietnam after fifteen years.

Their claims, however, rely on many unjustified

assumptions, including full employment in every

country and no resulting impacts on working people’s

incomes, with more than 90 percent of overall growth

gains due to ‘non-trade measures’ with varying

impacts.

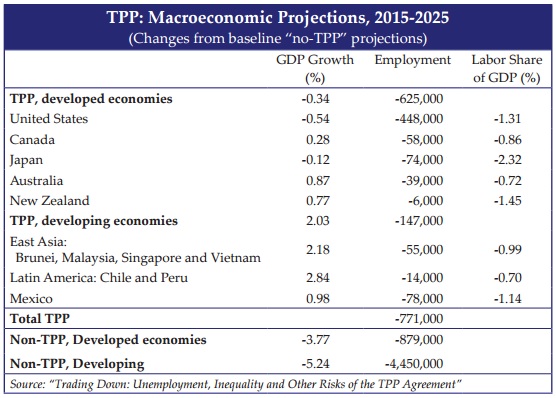

A recent GDAE

Working Paper finds that with more realistic

methodological assumptions, critics of the TPP

indeed have reason to be concerned. Using the trade

projections for the most optimistic growth

forecasts, we find that the TPP is more likely to

lead to net employment losses in many countries

(771,000 jobs lost overall, with 448,000 in the

United States alone) and higher inequality in all

country groupings. Declining worker purchasing power

would weaken aggregate demand, slowing economic

growth. The United States (-0.5 percent) and Japan

(-0.1 percent) are projected to suffer small net

income losses, not gains, from the TPP.

This GDAE

Policy Brief is intended to help clarify the

differences with other modeling studies and to

present our findings in a less technical manner.

Flaws in TPP Economic Projections

Optimistic claims about the TPP’s economic impacts

are largely based on economic modeling projections

published by the Washington-based Peterson Institute

for International Economics.2 Its

researchers used a computable general equilibrium

(CGE) model to project net GDP gains for all

countries involved. These figures have been widely

cited in many countries to justify TPP approval and

ratification. Updated estimates, released in early

2016 and incorporated into the World Bank’s latest

report on the global economy,3 now stress

income gains for the United States of $131 billion,

or 0.5 percent of GDP, and a 9.1 percent increase in

exports by 2030.4

The

projections methodology assumes away critical

economic problems and boosts economic growth

estimates with unfounded assumptions. The assumption

of full employment is particularly problematic.

Workers will inevitably be displaced due to the TPP,

but CGE modelers assume that all dismissed workers

will be promptly rehired elsewhere in the national

economy as if part of labor ‘churning’. The

full-employment assumption thus inflates projected

GDP gains by assuming away job losses and adjustment

costs.

The

modelers also dismiss increases in inequality by

assuming no changes to wage and profit shares of

national income. Again, this is not supported by

empirical evidence, as past trade agreements have

tended to reduce labor’s share.

Finally,

foreign direct investment (FDI) is assumed to

increase dramatically, which contributes a

significant boost to economic growth in the Peterson

Institute projections, accounting for more than 25

percent of projected U.S. economic gains in the

recent update. This assumes that: 1) income to

capital owners will be invested; and 2) this will

result in broad-based growth. Neither is supported

by the evidence. A U.S. Department of Agriculture

study,5 which did not assume such

FDI-related investment gains, found zero growth for

the United States and very modest growth elsewhere

at best.

The

methodology of the Peterson study is flawed;

consequently, growth and income gains are

overstated, and the costs to working people,

consumers and governments are understated, ignored

or even presented as benefits. Job losses and

declining or stagnant labor incomes are excluded

from consideration, even though they lower economic

growth by reducing aggregate demand.

Some

economists have pointed out6 additional

misleading findings in the most recent Peterson

Institute update:

• U.S.

income gains of 0.5 percent from TPP in 2030 –

This is raised from the institute’s previous 0.4

percent, mainly by extending the implementation

period from ten to fifteen years. In any case,

added growth of 0.5 percent is very small, about

0.03 percent per year over fifteen years.

•

Exports rise by 9.1 percent, but so do imports,

because the model assumes fixed trade balances.

This excludes, by assumption, the problems

associated with rising trade deficits, which

have been common after previous trade

agreements.

• All

displaced workers are absorbed immediately and

costlessly in other sectors – again, by

assumption. The paper does acknowledge that

manufacturing employment will increase more

slowly because of the TPP, and that some 53,700

more U.S. jobs per year will be “displaced”

annually. But they view this as a small addition

to normal labor market “churn.”

More Realistic Economic Projections

We employed

the UN Global Policy Model (GPM) to generate more

realistic projections of likely TPP impacts. Unlike

most CGE models, the GPM incorporates more realistic

assumptions about economic adjustment and income

distribution, assessing the TPP impact on each of

them as well as on economic growth over a ten-year

period. Importantly, it does not assume large

unexplained FDI surges or investment, growth and

income gains due to nontrade measures. The modeling

results are summarized in the table.

To

facilitate comparison, we used the Peterson

Institute’s projected estimates of the TPP’s impact

on exports, applying the macroeconomic model to

assess the efects of projected TPP trade increases.7

The GPM analyzes macroeconomic sectors – primary

commodities, energy, manufacturing and services –

but does not contain data on single markets (such as

car parts or poultry).

The main

fndings include:

• The

TPP will generate net GDP losses in the USA and

Japan. Ten years after the treaty comes into

force, US GDP is projected to be 0.54 percent

lower than it would be without the TPP.

Similarly, the TPP is projected to reduce

Japan’s growth by 0.12 percent.

• For

other TPP countries, economic gains will be

negligible – less than one percent over ten

years for developed countries, and less than

three percent over the decade for developing

countries. Chile and Peru’s combined gain of

2.84 percent comes to only about a quarter of

one percent per year.

• The

TPP is projected to lead to employment losses

overall, with a total of 771,000 jobs lost. The

United States will be hardest hit, losing

448,000 jobs.

• The

TPP will also likely lead to higher inequality

due to declining labor shares of national

incomes. In the United States, labor shares are

projected to fall by 1.31 percent over ten

years, continuing an ongoing multi-decade

downward trend.

Conclusions

In sum, the

TPP will increase pressures on labor incomes,

weakening domestic demand in all participating

countries, in turn leading to lower employment and

higher inequality. Even though countries with lower

labor costs may gain greater market shares and small

GDP increases, employment is still likely to fall

and inequality to increase.

In fact,

most goods trade among TPP countries has already

been liberalized by earlier agreements. Instead of

promoting growth and employment, the TPP is mainly

about imposing new rules favored by large

multinational corporations. The TPP greatly

strengthens investor and intellectual property

rights (IPRs), while weakening national regulation,

e.g. over financial services.

The TPP

will strengthen IPRs for big pharmaceutical,

information technology, media, and other firms, e.g.

by allowing pharmaceutical companies longer

monopolies on patented medicines, keeping cheaper

generics of the market, and blocking the development

and availability of similar new medicines.

The TPP

would also strengthen foreign investor rights at the

expense of local businesses and the public interest.

The TPP’s investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS)

system will oblige governments to compensate foreign

investors for losses of expected profits in binding

private arbitration.

These

pro-investor measures impose significant costs,

especially on developing countries. They will exert

a chilling efect on important government

responsibilities to promote national development and

protect the public interest.

Our

modeling suggests that TPP skeptics, concerned about

the agreement’s impacts on growth, labor incomes,

employment and inequality, have good reason to doubt

optimistic projections. Our results show negative

impacts in all these areas, particularly in the

United States. Legislatures in TPP countries should

carefully consider these findings and their

implications before approving the agreement.

Jomo Kwame Sundaram, an Assistant Secretary General

working on Economic Development in the United

Nations system during 2005-15, and was awarded the

2007 Wassily Leontief Prize for Advancing the

Frontiers of Economic Thought. Originally published

as a

Global Development and

Environment Institute Policy Brief

Endnotes

1 The

participating countries – Canada, United States,

Mexico, Chile, Peru, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia,

Singapore, Brunei, Australia and New Zealand – have

finalized and signed the text of the agreement, but

the treaty must be ratified in all of them before it

can come into force.

2 Peter

Petri, Michael Plummer and Fan Zhai (2012). “The

Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific

Integration: A Quantitative Assessment”. Policy

Analyses in International Economics 98, Peterson

Institute for International Economics, Washington,

DC. The Peterson Institute study has also been

criticized by others, e.g.

http://www.sustainabilitynz.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/EconomicGainsandCostsfromtheTPP_2014.pdf.

3 See

Global Economic Prospects, Spillovers Amid Weak

Recovery, January 2016, The World Bank Group,

Washington, DC.

4 Peter

Petri and Michael Plummer, “The Economic Efects of

the Trans-Pacifc Partnership: New Estimates”,

January 2016, Working Paper 16-2, Peterson Institute

for International Economics, Washington, DC.

5 See

http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1692509/err176.pdf

6 See, for

example, Dean Baker, “Peterson

Institute Study Shows TPP Will Lead to $357 Billion

Increase in Annual Imports”, January 26, 2016.

7 A robust

debate over such modeling followed the release of

the GDAE paper, with a critique from Robert Lawrence

for the Peterson Institute (“Studies

of TPP: Which is Credible?”) and two responses

from GDAE: “Are

the Peterson Institute Studies Reliable Guides to

Likely TPP Effects?” and “Modeling

TPP: A response to Robert Z. Lawrence.” GDAE

clarifed that the GPM is fully documented in the

UNCTAD publication, “The

UN Global Policy Model: Technical Description.”

|