|

Why Is

My Kindergartner Being Groomed for the Military at

School?

By Sarah Grey

February

05, 2016 "Information

Clearing House"

-

"Truth

Out" -

When

he got home from Iraq, Hart Viges began sorting

through his boyhood toys, looking for some he could

pass on to his new baby nephew. He found a stash of

G.I. Joes - his old favorites - and the memories

came flooding back.

"I thought

about giving them to him," he said. But the

pressures of a year in a war zone had strengthened

Viges' Christian faith, and he told the Army that

"if I loved my enemy I couldn't see killing them,

for any reason." He left as a conscientious

objector. As for the G.I. Joes, "I threw them away

instead." Viges had grown up playing dress-up with

his father's, grandfather's and uncles' old military

uniforms. "What we tell small kids has such a huge

effect," he told Truthout. "I didn't want to be the

one telling him to dream about the military."

As the

mother of a 6-year-old, I know what he means. My

partner and I, as longtime antiwar activists, work

hard to talk to our daughter about war, violence and

peace in age-appropriate ways.

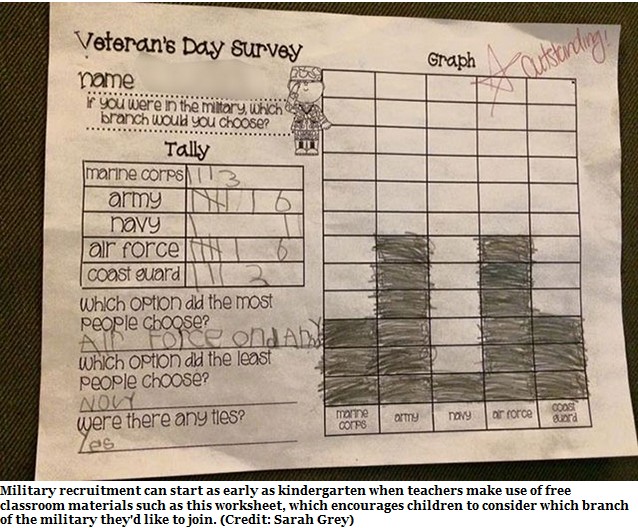

That's why

we were shocked this November when, shortly after

Veterans Day, our daughter came home from

kindergarten with a worksheet that asked the

children to decide which branch of the military they

would like to join. The class had been working on

charts in math class, taking polls and graphing the

results, which usually fell more along the lines of

what flavors of pie they preferred.

Military

recruitment can start as early as kindergarten when

teachers make use of free classroom materials such

as this worksheet, which encourages children to

consider which branch of the military they'd like to

join. (Credit: Sarah Grey)

Unsure what

to do, I posted a photo of the worksheet on Facebook,

with a simple caption: "I am not happy about this."

This kicked off a huge all-day debate on

Thanksgiving, with many commenters (especially those

abroad) expressing horror and others wondering what

the big deal was. Several identified the worksheet's

content as "grooming" children for later military

recruitment.

The US war machine is so

ubiquitous that few people even think twice about

its role in our children's lives.

Perhaps the

most insidious thing about this grooming is that it

wasn't even deliberate. The

worksheet did not come from military recruiters.

It didn't have to. Search online for "military

kindergarten printables" and you'll find a wealth of

free materials for teachers - a welcome resource in

cash-strapped public schools, where teachers often

pay significant sums out of pocket for classroom

materials.

My child's

teacher wasn't deliberately distributing propaganda.

When we talked with her about it, she was surprised

and very responsive. She's a fantastic teacher. It's

just that our country's

$598.5 billion war machine is so ubiquitous that

few people even think twice about its role in our

children's lives.

But we

should. It isn't just that the current wars are less

about "democracy" than about oil and empire. It

isn't just the body count, though that is

staggering: Researchers at the Costs of War Project

at Brown University

estimate 92,000 deaths in Afghanistan, 26,000 of

them civilians, with more than two-thirds of Afghans

now experiencing mental health problems. At least

165,000 Iraqi civilians have been

killed in the Iraq war since 2003. US drone

strikes have also killed about 3,800 people in

Pakistan, most of them civilians. That's in

addition to the estimated

6,800 US soldiers and 7,000 contractors who have

died, not to mention that Iraq and Afghanistan

veterans have filed nearly 1 million disability

claims with the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Jennifer

Smith, a mother of two teenage boys from Prospect

Park, Pennsylvania, responded to the worksheet by

asking:

How is

this teaching about Veterans Day? There's no

history on this worksheet. What there IS

however, is grooming. Having kindergartners

consider what branch they would be in? How is a

5 or 6 yr old supposed to make that decision?

What criteria is a kindergartner using?

Smith's

question is crucial. The most visible aspects of

military life are the things that make good toys:

ships, planes and tanks. But there's no warning on

toy boxes that a decade of constant war on multiple

fronts has left the US military stretched beyond its

capabilities, which means soldiers can be

involuntarily recalled: Active-duty personnel

routinely serve multiple tours of duty in Iraq

and Afghanistan. At least 16 percent of returning

veterans experience

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). US

Defense Department and RAND Corporation data show

that at least 5 percent of military women reported

being

raped or sexually assaulted, and that 62 percent

of those who reported a rape experienced retribution

or retaliation. And as for those great jobs

recruiters claim to offer? A

2014 investigation by NBC found that fully

one-quarter of active-duty military families

struggle with hunger and rely on food stamps, food

banks and other food aid to survive.

While we

can and should insist that recruiters be required to

present young people with stark realities like

these, it's important to understand that children's

images of and attitudes toward the military are

shaped long before they're old enough to be

considered legitimate targets for recruiters.

Recruiters are the tip of an enormous ideological

iceberg. Recruitment efforts run a lot deeper than

their visible presence in schools and shopping

malls. To see just how deep, you have to start at

the beginning.

The

all-volunteer army is a recent phenomenon in the

United States. From the Civil War until 1973, all

young men were required to register for the draft.

The Conscription Act, passed during World War I,

punished those who refused with prison sentences,

labor camps and even the death penalty,

according to historian Gerald Shenk. But even

before the US military needed to attract soldiers,

it was concerned with preparing children for

military service. The armed forces needed literate,

technically skilled recruits who could perform

increasingly complicated tasks. In his book

War Play, Corey Mead points out that this

need shaped the formation of the US public school

system - particularly its emphasis on standardized

testing. (Indeed, he points out that "the first

Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), given in 1926, was a

modified version of the army's Alpha exam.... Many

of the original test's questions made the military

connection explicit.")

The promise of an education, a

steady job and veterans' benefits lure young people

who don't have many other options.

Military

conscription - that is, the draft - ended in 1973,

the result of a strong, militant antiwar movement

that spread not only across the United States, but

among soldiers in Vietnam. Rick Jahnkow of

Project YANO (the Project on Youth and

Non-Military Opportunities) in San Diego,

California, an organization that addresses the

economic effects of militarism on communities, was

part of the Vietnam-era draft resistance movement.

He points out that the abolition of the draft - a

major blow to the military - marked the beginning of

recruitment by any means necessary. "The Pentagon

took a different tack," Jahnkow said, "because they

had to. They had to market soldiering in a whole

different way."

When the

stick failed - when the armed forces were prevented

from using the threat of prison, withholding

financial aid and other punishments to force young

people into the ranks - they turned to the carrot.

Promises of scholarships, marketable skills, bonus

money and a chance to "see the world" or help the

victims of global conflicts became inducements to

sign up.

The promise

of an education, a steady job and veterans' benefits

lure young people who don't have many other options.

It's often called the "economic draft." Kids who

can't afford college or who face grim job prospects

in a declining economy are far more likely to join

the military; that's why recruiters are far more

active in low-income areas. Veteran and activist

Tomas Young told biographer Mark Wilkerson, "There

was no other way that I could go to college without

having to pay back monstrous student loans.... My

plan was to serve my time, take my GI Bill money and

go to school in Oregon or someplace." Young never

got the chance to go to school. As the forthcoming

book

Tomas Young's War documents, he was

paralyzed by a bullet in Sadr City on his fifth day

in Iraq. He spent the rest of his short life

campaigning with

Iraq

Veterans Against the War to the extent his

excruciatingly painful injuries allowed. He died in

2014.

The promise

of education and jobs is a powerful lure. But to get

that message across to potential soldiers, military

recruiters had to reach them. They couldn't afford

to hang around in recruitment offices waiting; they

had to go where the kids were, and that meant

getting inside the schools.

Shifts in legislation over the

past decade and a half have opened schools up to the

military more than ever before.

In the

1970s and 1980s, this was often accomplished on a

school-by-school basis. Recruiters asked for

permission to set up tables in high school

cafeterias and signed up for career fairs. Their

access was regularly challenged by parents and

community groups like Project YANO. But the first

Gulf War shifted the terms of the debate. The

military's role in schools wasn't just about open

recruiting anymore; it was about "supporting the

troops" with exercises like yellow-ribbon campaigns,

assemblies and postcard-writing competitions. Since

these weren't explicit recruitment activities,

restrictions about students' ages and grade levels

didn't apply; even the youngest children could

participate.

In the

1990s, these strategies were applied more widely,

according to Jahnkow. As schools began to initiate

"partnerships" with local businesses and nonprofit

organizations, military recruiters applied to

participate in such programs, arguing that they were

simply one more organization and deserved equal

consideration. Often, however, such partnerships

served as a guise for open recruitment of young

children.

Jahnkow

provided me with a copy of a memo Project YANO sent

the school board of the San Diego Unified School

District on March 6, 1992. A school in the district,

Horton Elementary, had embarked on a partnership

with a local US Navy unit. "Early in December [1991]

a man appeared at Horton Elementary dressed as Santa

Claus," the memo recounted.

Apparently, he was a representative of the Navy.

According to children who were there that day,

this "Santa Claus" distributed bags of material

to many, if not all, of the children at the

school (K-6).

What

horrified some parents was that "Santa"

distributed military recruiting propaganda in

the bags given to their children. We have a copy

of one of the items, a Navy folder that is

clearly designed as a recruiting tool ...

The

Horton principal has also admitted that military

tanks have been brought to career events at the

school and children have been allowed to crawl

through them! After telling this to one parent,

he reassured her that the children are not

allowed to bring toy guns to school. Wonderful

logic, isn't it?

Showing off

military equipment is a favorite tactic. Hart Viges,

who is now an active member of Iraq Veterans Against

the War and

Sustainable Options for Youth, recalls a

military helicopter being displayed at his

elementary school in the 1990s. "We thought it was

so cool," he said. "Of course, they didn't tell us

it was a killing machine."

Defense

Department-sponsored after-school programs like

STARBASE reach children as young as grade 5,

offering tutoring (by uniformed soldiers) and

"increased career awareness," with an

explicitly stated mission to "expose our

nation's youth to the technological environments and

positive civilian and military role models found on

Active, Guard, and Reserve military bases and

installations."

The Junior

ROTC program targets middle school and high school

students with military drills and training. In

Chicago, the public school system is even

experimenting with

publicly funded JROTC military academies. Each

academy focuses on a specific military branch and is

partially staffed by retired military personnel. The

Chicago program's website claims that "although

students wear uniforms and operate in a structured

environment, these schools are not intended to

prepare students for the military."

Shifts in

legislation over the past decade and a half have

opened schools up to the military more than ever

before. Just after 9/11, President George W. Bush

signed into law the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act

of 2001. The act, which has since been renewed by

President Obama, took drastic measures to implement

standardized curricula and testing in the nation's

public schools. It also gives recruiters

unprecedented leeway,

according to a report by the Constitutional

Litigation Clinic at the Rutgers School of Law:

"schools receiving federal funds must give military

recruiters the same access to students as

they give employers and college recruiters,"

including the names of all junior and senior

students.

Parents can

sign a form to "opt out" of giving recruiters access

to their child's time and information, and "the NCLB

and Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act

(FERPA) require that parents be told that they have

the right to keep recruiters away from their

children." However, according to the Rutgers report,

"high schools throughout the State [of New Jersey]

do not notify parents of this right adequately, or

at all." In addition, the report found that "schools

throughout the State give recruiters much greater

access to students than is required by law" and that

"lack of oversight allows recruiters to present

students with unrealistic and false portrayals of

military service." A

report from the US Army War College arguing in

favor of unfettered recruiting notes that "access to

the high school population remains critical to DoD

[Defense Department] efforts to man the force as

propensity for military service drops dramatically

for most groups after the age of 18."

Toys, video games, sports, TV

shows and movies all normalize not only the military

but combat itself.

The

Department of Defense also maintains contracts with

private corporations that broker data about

children: Journalist David Goodman

told Democracy Now! in 2009 that this

information includes everything from "when you buy a

yearbook, when you buy a student ring ... any number

of ... commercial purchases." Data brokers'

information,

he writes, is combined with data from the

Selective Service, state DMVs, the ASVAB

standardized test and information children

voluntarily provide to "career planning" websites

openly or not-so-openly run by recruiters, such as

myfuture.com and march2success.com. The result is a

remarkably detailed picture that allows recruiters

to screen out kids who don't qualify (due to

physical fitness, criminal records or other factors)

and target the ones who do.

Access to

schools isn't the only route into children's lives,

however. The Department of Defense spends billions

each year on video game development, as Mead's book

documents. The Army has even developed its own

realistic simulation game, "America's Army," and

recruiters give kids access to trailers full of

video game consoles where they can play it.

There's

also the

$10.4 million the military has spent on marketing

displays at pro football, baseball, hockey,

basketball and soccer games since 2012 - not to

mention that "the National Guard spent more than $56

million each year on sports marketing with NASCAR

and IndyCar,"

according to The Washington Post.

Then

there's sponsoring and consulting on Hollywood films

(a partnership that goes back to the dawn of the

film industry). Journalist Nick Turse, in his book

The Complex, quotes Transformers

(2007) producer Ian Bryce enthusing about the

movie's Pentagon ties: "We want to cooperate with

the Pentagon to show them off in the most positive

light, and the Pentagon likewise wants to give us

the resources to be able to do that."

These

efforts reach kids as young as preschool, priming

them to think of war and soldiering as cool and

exciting, without any discussion of the trauma and

death they are designed to bring. Hart Viges vividly

remembers playing with soldier toys while watching

"G.I. Joe," a cartoon show that ran from 1983 to

1986. "I actually went back and watched a bunch of

episodes on Netflix, just to see what was put into

my head," he said. "It was weirdly specific - like,

there were at least three episodes where they talked

about how they couldn't fight Cobra [the villains'

organization] because the G.I. Joe budget was coming

under attack."

Toys, video

games, sports, TV shows and movies all normalize not

only the military but combat itself. Though there's

intense debate over the topic,

studies have shown that first-person shooter

games do desensitize heavy players to images of

violence - unsurprisingly, it's easier to imagine

shooting someone when you spend all day simulating

shooting someone. Allowing children to play in tanks

and imagine themselves at the controls likewise

lowers their inhibitions, especially since this

exposure to big, exciting machines is not

accompanied by any way of envisioning the killing

and devastation the machines are designed to deal

out. Likewise, classroom discussions of military

careers that don't inform children about the

realities of war have the effect of inviting

children to fantasize about war - priming them to

welcome the advances of recruiters whose goal is to

lure them into a war machine that is likely to leave

them to poverty, pain, PTSD and an early grave.

So what can

students, parents and others do to stop military

grooming? Dr. Terrence Webster-Doyle, a Vietnam

veteran,

Veterans for Peace member and founder of the

Youth Peace Literacy program, writes free books

for children and adults about ending the cycle of

violence. He also

advocates martial arts training as a way to

allow youth to channel their aggression in a safe,

controlled environment.

The most

effective solution, Viges says, is

counter-recruitment. Viges mans a Sustainable

Options for Youth table in Austin, Texas, high

school cafeterias, where he offers stark statistics

about sexual assault, PTSD, veteran homelessness and

other less attractive aspects of military life and

gives out information about a range of alternative

job opportunities, from firefighting to AmeriCorps.

Project YANO sends veterans to speak to

schoolchildren and youth groups about the realities

of war, as well as alternatives for jobs and college

funding, and educates school administrators about

recruiters' tactics. Viges has also been known to

slap warning stickers on the boxes of games like

"America's Army" at Walmart.

As parents,

we should question what our kids are told about war

and the military in school, on TV and even through

the toys we give them. We should also present them -

and their teachers - with all of the facts, even the

ugly ones. They might still choose to sign up as

teenagers, but we can at least make sure they make

fully informed decisions.

Afghanistan

veteran and war resister Rory Fanning, author of

Worth Fighting For, spent nine months

walking on foot across the United States to raise

money for the

Pat Tillman Foundation, a scholarship fund for

veterans and their families named for the former NFL

star turned Army Ranger, whose death by friendly

fire

resulted in a scandal for the Pentagon.

Fanning's journey became one of counter-recruitment

when he spoke to students in Roby, Texas. "Which

branch of the military should I join?" one boy asked

- and Fanning surprised himself by responding, "I

don't think you should join any of them."

That wasn't

an option on my daughter's worksheet. Let's make

sure children of all age groups know that they have

the right to say no to war, to violence and to

military recruiters.

Sarah

Grey is a freelance writer and editor in

Philadelphia, an antiwar activist and the parent of

a kindergarten student. Her writing on politics,

language and food has been published in Best Food

Writing 2015, Truthout, The Establishment, Serious

Eats, Lucky Peach, Spoonful, The Frisky,

Copyediting, and many more. |