Is There a Human Right to

Kill?

How governments, NGOs, and conservative think tanks turned the

language of human rights on its head.

By Neve Gordon

EDITOR'S NOTE: In their new

book,

The Human Right to Dominate,

Nicola Perugini and Neve Gordon trace the way human

rights—generally conceived as a counter-hegemonic

instrument for righting historical injustices—are being

deployed to further subjugate the weak and legitimize

domination. What follows is a short adaptation of the

first and third chapters.

July 08, 2015 "Information

Clearing House"

-

"The

Nation" -

On

a cool spring day in May 2012, the members of the North Atlantic

Treaty Organization (NATO) met in McCormick Place, Chicago. The 28

heads of state comprising the military alliance had come to the

Windy City to discuss the withdrawal of NATO forces from

Afghanistan, among other strategic matters. Nearly a decade before,

in August 2003, NATO had assumed control of the International

Security Assistance Force, a coalition of more than 30 countries

that had sent soldiers to occupy the most troubled regions in

Afghanistan. Not long before the Chicago summit, President Barack

Obama had publicly declared that the United States would begin

pulling out its troops from Afghanistan and that a complete

withdrawal would be achieved by 2014. NATO was therefore set to

decide on the details of a potential exit strategy.

A few days before the summit, placards appeared in

bus stops around downtown Chicago urging NATO not to withdraw its

forces from Afghanistan. “NATO: Keep the progress going!” read the

posters. The caption was spread over a photograph of two Afghan

women wearing burkas that covered their entire body, including head

and face. Walking between them is a girl who seems surprised by the

voyeuristic photographer; hers is the only visible face, which looks

neither frightened nor happy, but is nonetheless alert. The

photograph’s subtext seems clear: The burka is this child’s future.

Connecting the caption with the image, one understands that,

according to the logic of the placard, NATO needs to continue its

mission in Afghanistan in order to emancipate Afghan women,

particularly Afghan girls.

The

poster was part of a public campaign against President Obama’s

declared intention of withdrawing US and NATO troops from

Afghanistan. Under the banner “NATO: Keep the progress going!” there

was notification about a “Shadow Summit for Afghan Women” that was

to take place alongside the NATO summit. Sponsoring the event was

not a Republican think tank or a defense corporation, such as

Lockheed Martin, but Amnesty International, the first and one of the

most renowned human-rights organizations across the globe.

The

poster was part of a public campaign against President Obama’s

declared intention of withdrawing US and NATO troops from

Afghanistan. Under the banner “NATO: Keep the progress going!” there

was notification about a “Shadow Summit for Afghan Women” that was

to take place alongside the NATO summit. Sponsoring the event was

not a Republican think tank or a defense corporation, such as

Lockheed Martin, but Amnesty International, the first and one of the

most renowned human-rights organizations across the globe.

Amnesty also prepared a letter that emphasized the

importance of NATO’s continued intervention in Afghanistan and

managed to secure the signature of former secretary of state

Madeleine Albright, among others. During the shadow summit itself,

participants made remarks that dovetailed nicely with the US State

Department’s “Responsibility to Protect” doctrine, otherwise known

as “humanitarian intervention.”

The idea that the most prominent international

human rights NGO was campaigning against the withdrawal of US and

NATO military forces from a country halfway around the globe is

something worth dwelling on. The assumption underlying Amnesty’s

campaign that the deployment of violence is necessary to protect

human rights suggests that violence and human rights are not

necessarily antithetical. Violence protects human rights from the

violence that violates human rights. Violence is not only the source

of abuse but, as Amnesty’s placard clearly implies, can also be the

source of women’s liberation. Yet if violence is traditionally

associated with domination and human rights with emancipation, then

the connection between the two seems odd. Are human rights

unavoidably connected to domination, or is this campaign just an

exceptional case?

Amnesty International’s campaign against the

withdrawal of NATO troops from Afghanistan is merely a paradigmatic

example of a much wider trend whereby human rights are being

deployed in the service of domination. If during the 1980s and

1990s, conservatives in the United States tended to reject the

expanding human-rights culture and were often even hostile to it, at

the turn of the new millennium they began to alter their strategy,

embracing human-rights language.In few

areas is this more pronounced than in the widening overlap between

human rights and the laws and rituals of war. “Once considered

obstacles to the war effort,” according to human-rights law scholar

Thomas W. Smith, “military lawyers [and human rights experts] have

been integrated into strategic and tactical decisions, and even

accompany troops into battle.” Indeed, we are now living in an era

where human rights are frequently used by the state, and by

conservative and even by liberal human rights organizations, to

“civilize,” in Achille Mbembe’s words, “the ways of killing and to

attribute rational objectives [and justifications] to the very act

of killing.”

The Human Right to Kill

The “unprecedented public scrutiny” that military

forces have been subjected to in recent years triggered a pedagogic

process in which men and women in uniform started learning through

multiple ad hoc education programs the philosophical and moral

foundations of the deployment of violence. International human

rights and humanitarian law occupy a prominent position in these

programs. Indeed, human-rights classes are often mandatory in the US

military, while the government trains each year approximately

100,000 foreign police and soldiers from more than 150 countries.

The interesting issue for us is not so much that human-rights

professionals train soldiers, but rather that human-rights NGOs and

militaries converge with respect to the use of human rights as an

epistemic and moral framework for judging the significance of

killing within a given context.

Prominent Harvard law professor David Kennedy

describes the human-rights training programs run by the US military

in recent decades as courses in which the message is clear: “This is

not some humanitarian add-on—a way of being nice or reducing

military muscle,” he says. “We asserted, with some justification,

that it is simply not possible to use the sophisticated

weapons one purchases or to coordinate with the international

military operations in which they would be used without an internal

military culture with parallel rules of operation and engagement.”

An expert on the relation between international

humanitarian and human-rights law and war, Kennedy has gained a

considerable amount of experience and public recognition working

with numerous human-rights organizations as well as with the US

military and other armed forces. As early as 1996, he travelled to

Senegal as a civilian instructor with the Naval Justice School “to

train members of the Senegalese military in the laws of war and

human rights.” At the time, he notes, “The training program was

operating in fifty-three countries, from Albania to Zimbabwe.”

Describing the message conveyed to the trainees in these countries,

he writes: “We insisted, humanitarian law will make your military

more effective—will make your use of force something you can sustain

and proudly stand behind.”

Kennedy’s ongoing reference to a “we,” whereby the

well known law professor simultaneously portrays and considers

himself as part of the military machine waging civilized wars, is

not an oversight. To be sure, Kennedy, who called one of his books

The Dark Sides of Virtue, is aware of the uncomfortable

complicity between those who are trained to kill and those who are

trained to defend human rights. But this complicity—the fundamental

and recurrent convergence of human rights and violent forms of

domination—is a conundrum that needs to be further interrogated

beyond the questions that Kennedy asks in his pragmatist effort to

make the international human-rights movement more coherent and

effective.

Kennedy maintains in his book that, in order to

participate in the international military profession, one has “to

learn its new humanitarian vocabulary. We had no idea, of course,

what it meant in their culture [i.e., of militaries of

other countries] for violence to be legitimate, effective, something

one could stand behind proudly. But they had learned something of

what that meant in their culture of global humanitarian and military

professionalism.” What stands out in Kennedy’s description of the US

military’s training program is that human rights and military

professionalism are not part of antithetical spheres informed by an

opposing ethos, but are or have become part of the same political

culture that aims to produce a specific ethics of violence.

Not unlike its American counterpart, the Israeli

military also emphasizes its concern with human rights and

humanitarianism. On its official blog it describes, for example, how

over the years “the IDF ’s humanitarian aid has served as a source

of relief for people all over the world.” The blog notes that an IDF

rescue delegation just returned (November 2013) from 12 days in the

Philippines, assisting civilians in Bogo City whose lives were

uprooted by Typhoon Haiyan. “Upon arrival,” the blog post continues,

“IDF doctors immediately set up a field hospital, where they treated

over 2,600 patients, performed 60 surgeries, delivered 36 babies,

and worked on repairing schools damaged by the storm.”

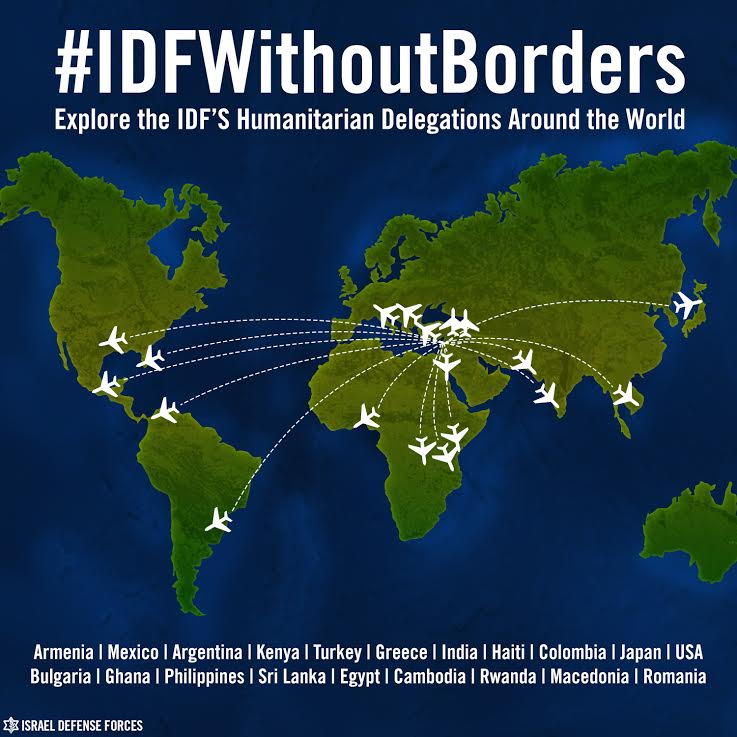

The blog’s readers are then referred to a map in

order to “discover the long history of IDF aid delegations all

around the world.” The poster, entitled “#IDFWithoutBorders,”

mirrors the motto of Doctors Without Borders, perhaps the most

prominent humanitarian organization in the world. The Israeli

military, which for years has been an instrument of domination in

the Occupied Palestinian Territories, is thus cast within a moral

framework of global humanitarianism.

Considering that attempts to regulate war are “as

old as war itself,” this convergence between killing and

humanitarian aid is the culmination of a long process. Over the past

decades legal experts, munitions experts, medical doctors,

philosophers, statisticians, and, more recently, human-rights

professionals have been working together to continuously develop

additional treaties and ethical codes to regulate and refine the

methods and means of warfare, and, purportedly, to protect civilians

as well as combatants in armed conflict. Simultaneously, leading

academic institutions and think tanks have been organizing

conferences and workshops that bring together these diverse experts

and thus have helped to produce a shared space where a common

culture of ethical warfare can develop.

A

paradigmatic example is the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at

Harvard, which helped the US military revise its counterinsurgency

field manual. Following vocal criticism, Sarah Sewall, the Center’s

faculty director who wrote an introduction to the manual and had

previously been a Pentagon official, explained that faculty members

were trying to instill institutional change within the military.

This convergence between human-rights discourse (informed by the

imperative to protect civilians) and forms of legal killing is

constantly deepening, for, as Kennedy describes in his books,

militaries the world over are inviting human-rights experts to give

talks and offer advice about what is permissible and impermissible

in contemporary warfare. In this way they not only regulate the

forms of killing but also offer the state itself protection from

accusations that its way of killing violated international law.

A

paradigmatic example is the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at

Harvard, which helped the US military revise its counterinsurgency

field manual. Following vocal criticism, Sarah Sewall, the Center’s

faculty director who wrote an introduction to the manual and had

previously been a Pentagon official, explained that faculty members

were trying to instill institutional change within the military.

This convergence between human-rights discourse (informed by the

imperative to protect civilians) and forms of legal killing is

constantly deepening, for, as Kennedy describes in his books,

militaries the world over are inviting human-rights experts to give

talks and offer advice about what is permissible and impermissible

in contemporary warfare. In this way they not only regulate the

forms of killing but also offer the state itself protection from

accusations that its way of killing violated international law.

Israel is, of course, no exception. Working

together with the Israeli military, philosophy professor Asa Kasher

of Tel Aviv University formulated guidelines outlining when it is

ethical to “assassinate in fighting terror.” The right to

assassinate, according to Kasher, is grounded by the obligation of

the state to protect the human rights of its citizens, including the

right to life. Put differently, assassinations are carried out

within the framework of human rights (i.e., morally permissible)

when they satisfy two forms of protection: the protection of the

citizens by the state and the protection of the state itself. Human

rights serve as the justification for killing and thus transform

killing into a right.

One of the patent manifestations of this

convergence is the widespread phenomenon of bringing experts in

international humanitarian and human-rights law into the war room

and bestowing upon these lawyers the authority to make decisions

that directly affect combat. It appears that the 1991 Gulf War was a

watershed in this respect, with some 200 lawyers being brought in to

work in the US Army’s theater of operations, ensuring that military

decisions “were impacted by legal considerations at every level.”

In Israel, this has also become common practice.

Following the 2014 war in Gaza, one of Israel’s first conclusions

was that the IDF ’s international legal department had to be further

enlarged. In a 2013 magazine interview, Zvi Hauser, Israel’s former

cabinet secretary and longtime aide to Prime Minister Benjamin

Netanyahu, revealed the level of influence lawyers with expertise in

international law have in the Israeli decision-making process. He

described in detail a meeting in the days preceding the attempt of

the Mavi Marmara, an unarmed ship manned by mostly Turkish citizens,

to break Israel’s military siege on the Gaza Strip in order to

provide humanitarian aid to its Palestinian residents.

In contrast to others, I said: “Wait a minute,

why shouldn’t we allow this unarmed ship to enter Gaza?” I did

not anticipate the nine [Turkish citizens that would be] killed,

but I didn’t understand why we had to play the bad guy part for

which we were cast by the Turks in that bad movie. I know the

prime minister. I saw in his eyes that he grasped the situation.

Netanyahu likes to hear out-of-the-box ideas. But the jurists in

the meeting argued that from the legal aspect, as long as a

closure was in effect, Israel was obliged to enforce it. End of

discussion. The political decision-makers don’t think they can

make a decision that is contrary to the imperative of the

judicial level.

The humanitarian maritime convoy was stopped by

Israeli combat units, which, according to Israeli legal experts,

abided by international law when they killed nine civilians who were

on the Mavi Marmara. This process whereby experts in international

humanitarian and human-rights law influence decisions that bear

directly on combat has not been unidirectional but rather

reciprocal. Parallel to the military’s incorporation of a

humanitarian logic, human-rights NGOs have been utilizing military

know-how and military rationales to advance their goals.

As Eyal Weizman points out, human rights NGOs have

also begun integrating military theory and knowledge into their

work, using, for example, munitions experts to gather evidence about

the kind of bombs utilized to demolish houses in the Gaza Strip.

From a slightly different perspective, it was Amnesty International

USA’s former executive director, Suzanne Nossel, who launched the

campaign against NATO’s imminent withdrawal from Afghanistan,

claiming that military force helps to protect women’s rights. Nossel

was hired by the Obama administration as the deputy assistant

secretary of state for international organization affairs and from

there she moved on to Amnesty International. This relocation is

interesting because it reveals that Amnesty and the State Department

occupy social spaces that are not all that distant from each other.

In the first case, then, the human-rights

organization hires a munitions expert as an authority on violence,

while in the second case the human-rights organization hires a State

Department official who encourages the deployment of violence as a

way of protecting human rights. It is accordingly not only the

military that mobilizes a humanitarian vocabulary of international

law and uses it as a strategic asset, but also human-rights

organizations that use the military vocabulary, knowledge, and logic

to protect human rights.

This discursive and practical proximity

underscores that a culture of ethical violence is coalescing; one in

which human rights, humanitarianism, and domination are intricately

tied. The extent of this propinquity makes it, at times, difficult

to understand if human rights and humanitarianism are regulating

violence or whether violence is determining the parameters of human

rights. In this brave new rights-based world, in other words, human

rights are not the other side of killing, and killing is not

necessarily the other side of human rights.

Nicola Perugini Nicola

Perugini is Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Italian Studies and Middle

East Studies at Brown University and co-author with Neve Gordon of The

Human Right to Dominate. Follow

Nicola on Twitter: @PeruginiNic.

Neve Gordon Neve Gordon is

the author of Israel’s

Occupation (2008) and recently completed, with Nicola Perugini,

The Human Right to Dominate

(forthcoming from Oxford University Press).

Copyright © 2015 The Nation