Real Unemployment is

Double the ‘Official’ Unemployment Rate

By Pete Dolack

March 20, 2015 "ICH"

- How many people are really out of work?

The answer is surprisingly difficult to

ascertain. For reasons that are likely

ideological at least in part, official

unemployment figures greatly under-report

the true number of people lacking necessary

full-time work.That

the “reserve army of labor” is quite large

goes a long way toward explaining the

persistence of stagnant wages in an era of

increasing productivity.

How large? Across North

America, Europe and Australia, the real

unemployment rate is approximately double

the “official” unemployment rate.

The “official”

unemployment rate in the United States, for

example, was 5.5 percent for February 2015.

That is the figure that is widely reported.

But the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

keeps track of various other unemployment

rates, the most pertinent being its “U-6”

figure. The U-6 unemployment rate includes

all who are counted as unemployed in the

“official” rate, plus discouraged workers,

the total of those employed part time but

not able to secure full-time work and all

persons marginally attached to the labor

force (those who wish to work but have given

up). The actual U.S. unemployment rate for

February 2015, therefore,

is 11 percent.

Canada makes it much more

difficult to know its real unemployment

rate. The

official Canadian unemployment rate for

February was 6.8 percent, a slight increase

from January that Statistics Canada

attributes to “more people search[ing] for

work.” The official measurement in Canada,

as in the U.S., European Union and

Australia, mirrors the official standard for

measuring employment defined by the

International Labour Organization — those

not working at all and who are “actively

looking for work.” (The ILO is an agency of

the United Nations.)

Statistics Canada’s

closest measure toward counting full

unemployment is its R8 statistic, but the R8

counts people in part-time work, including

those wanting full-time work, as “full-time

equivalents,” thus underestimating the

number of under-employed by hundreds of

thousands,

according to an analysis by The

Globe and Mail. There are further

hundreds of thousands not counted because

they do not meet the criteria for “looking

for work.” Thus The Globe and Mail

analysis estimates Canada’s real

unemployment rate for 2012 was 14.2 percent

rather than the official 7.2 percent. Thus

Canada’s true current unemployment rate

today is likely about 14 percent.

Everywhere you

look, more are out of work

The gap is nearly as large

in Europe as in North America. The official

European Union unemployment rate was

9.8 percent in January 2015. The

European Union’s Eurostat service requires

some digging to find out the actual

unemployment rate, requiring adding up

different parameters. Under-employed workers

and discouraged workers comprise four

percent of the E.U. workforce each, and if

we add the one percent of those seeking work

but not immediately available, that pushes

the

actual unemployment rate to about 19

percent.

The same pattern holds for

Australia. The Australia Bureau of

Statistics revealed that its measure of

“extended labour force under-utilisation” —

this includes “discouraged” jobseekers, the

“underemployed” and those who want to start

work within a month, but cannot begin

immediately — was

13.1 percent in August 2012 (the latest

for which I can find), in contrast to the

“official,” and far more widely reported,

unemployment rate of five percent at the

time.

Concomitant with these

sobering statistics is the length of time

people are out of work. In the European

Union, for example, the long-term

unemployment rate — defined as the number of

people out of work for at least 12 months — doubled

from 2008 to 2013. The number of U.S.

workers unemployed for six months or longer

more than tripled from 2007 to 2013.

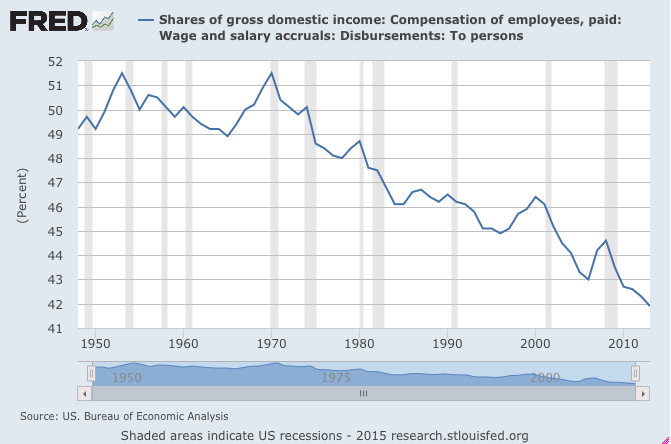

Thanks to the specter of

chronic high unemployment, and capitalists’

ability to transfer jobs overseas as “free

trade” rules become more draconian, it comes

as little surprise that the share of gross

domestic income going to wages has declined

steadily. In the U.S., the share has

declined from 51.5 percent in 1970 to about

42 percent. But even that decline likely

understates the amount of compensation going

to working people because almost all gains

in recent decades has gone to the top one

percent.

Around the world,

worker productivity has risen over the past

four decades while wages have been

nearly flat. Simply put, we’d all be making

much more money if wages had merely kept

pace with increased productivity.

Insecure work is

the global norm

The increased ability of

capital to move at will around the world has

done much to exacerbate these trends. The

desire of capitalists to depress wages to

buoy profitability is a driving force behind

their push for governments to adopt “free

trade” deals that accelerate the movement of

production to low-wage, regulation-free

countries. On a global basis, those with

steady employment are actually a minority of

the world’s workers.

Using International Labour

Organization figures as a starting point,

professors John Bellamy Foster and Robert

McChesney calculate that the “global reserve

army of labor” — workers who are

underemployed, unemployed or “vulnerably

employed” (including informal workers) —

totals 2.4 billion. In contrast, the world’s

wage workers total 1.4 billion — far less!

Writing in their book

The Endless Crisis: How Monopoly-Finance

Capital Produces Stagnation and Upheaval

from the USA to China, they write:

“It is the existence

of a reserve army that in its maximum

extent is more than 70 percent larger

than the active labor army that serves

to restrain wages globally, and

particularly in poorer countries.

Indeed, most of this reserve army is

located in the underdeveloped countries

of the world, though its growth can be

seen today in the rich countries as

well.” [page 145]

The earliest countries

that adopted capitalism could “export” their

“excess” population though mass emigration.

From 1820 to 1915, Professors Foster and

McChesney write, more than 50 million people

left Europe for the “new world.” But there

are no longer such places for developing

countries to send the people for whom

capitalism at home can not supply

employment. Not even a seven percent growth

rate for 50 years across the entire global

South could absorb more than a third of the

peasantry leaving the countryside for

cities, they write. Such a sustained growth

rate is extremely unlikely.

As with the growing

environmental crisis, these mounting

economic problems are functions of the need

for ceaseless growth. Once again, infinite

growth is not possible on a finite planet,

especially one that is approaching its

limits. Worse, to keep the system

functioning at all, the

planned obsolescence of consumer products

necessary to continually stimulate household

spending accelerates the exploitation of

natural resources at unsustainable rates and

all this unnecessary consumption produces

pollution increasingly stressing the

environment.

Humanity is currently

consuming the

equivalent of one and a half earths,

according to the non-profit group Global

Footprint Network. A separate report by

WWF–World Wide Fund For Nature in

collaboration with the Zoological Society of

London and Global Footprint Network,

calculates that the Middle East/Central

Asia, Asia-Pacific, North America and

European Union regions are each

consuming about double their regional

biocapacity.

We have only one Earth.

And that one Earth is in the grips of a

system that takes at a pace that, unless

reversed, will leave it a wrecked hulk while

throwing ever more people into poverty and

immiseration. That this can go on

indefinitely is the biggest fantasy.

Pete Dolack is an

activist, writer, poet and photographer.

https://systemicdisorder.wordpress.com/