By Matthew Stevenson

June 18, 2020 "Information

Clearing House" - If the prospect of the

Trump – Biden presidential election fills you with

horror and despair, you might give some thought to not

just replacing both candidates but the presidency as

well, at least as we now conceive it.

For some time now, but maybe since the Kennedy

administration (which ended in a hail of

voter-suppressed gunfire), I have been thinking that one

of the biggest problems with American democracy is the

presidency itself, the idea that the chief magistrate of

the country should be one person elected every four

years by a few swing voters in Ohio, North Carolina, or

Florida.

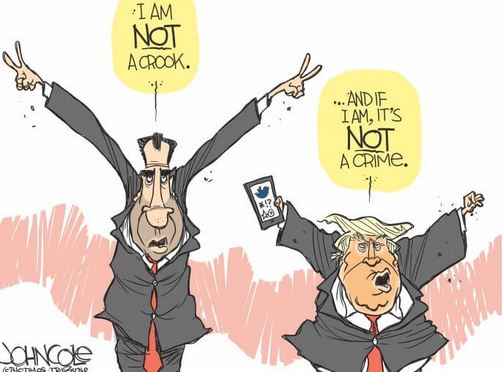

What good can be said of an office that regularly is

awarded to the likes of Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon,

and George W. Bush, and that this year, for its

finalists, has Donald Trump and Joe Biden, men who

otherwise would not be eligible to coach Little League

teams or lead Scout troops (pussy grabbers and hair

sniffers need not apply).

Instead, every four years, because of a document

drawn up more than two hundred years ago, the United

States puts into its highest office men of stunning

incompetence (think of W’s facial expression while

reading The Pet Goat on 9/11) and low cunning

(“Ike likes Nixon and we do too…”), who over

time have managed to turn the office of the presidency

into what it is today—a violent reality show that has

brought you Vietnam, Watergate, the USA Patriot Act, and

Barack Obama’s “necessary war” in Afghanistan.

According to James Madison’s notes from the 1789

constitutional convention, the job of the American

president was to “execute” the laws that Congress

passed. In times of war, the president was to serve as

the commander-in-chief of the state’s militias—to

exercise civilian control over the military.

At the Philadelphia constitutional convention, the

dispute about the presidency concerned which model to

follow in creating a template of the chief executive.

John Adams and Alexander Hamilton aspired to create a

constitutional monarchy of sorts, with their favorite

aristocrat, George Washington, on the throne.

At the very least they were in favor of a strong,

lone-wolf executive with centralized powers, while

Benjamin Franklin (with the emotional support of Thomas

Jefferson from Paris) and others favored a federal

council, something closer to the Swiss model, in which

the powers of the chief magistrate would be devolved to

a committee, not on one person.

James Madison, who had loyalties in both camps and a

heavy hand in drafting the new constitution, came up the

compromise and helped to shape the American presidency

that we know today—that of an elected monarch.

In Philadelphia in 1789, the constitutional framers

had hoped they were creating an office-holder along the

lines of an auditor-in-chief, someone who would make

sure that the Congress (notably the House of

Representatives) spent the people’s money wisely and

kept the trade lines flowing through (tariff-free)

interstate commerce.

It never occurred to any of them that they were

creating a monster along the lines of a political

Frankenstein who might someday, as if with bolts

protruding from his neck and an awkward square haircut,

stump his way though Lafayette Square and hold up a

Bible in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church.

|

Are You Tired Of

The Lies And

Non-Stop Propaganda?

|

***

Another problem with the original intent of the

presidency in the U.S. Constitution is that it was a

laissez-passer for slaveholders in southern states

(not to mention their cotton brokers in New York City)

to do pretty much as they pleased in terms of exploiting

the means of production.

Until the corporate railroad lawyer Abraham Lincoln

came along, American presidents functioned as trustees

for slaveowners, and nearly all (in the manner of James

Buchanan during the era of Dred Scott, the runaway slave

of Supreme Court fame) bent over backwards to insure

that indentured service remained an unenumerated right

of the moneyed classes.

A few presidents, Andrew Jackson being one of them

during the 1832 Nullification Crisis, pushed back

against the notion of states’ rights, but

Jackson—himself a slave owner—made up for the hurt

Southern feelings by ethnically cleansing Florida and

Georgia of the Cherokee Nation, and turning over the

rich soil of its land to his slave-holding brethren.

Only Lincoln decided that the constitution

(tolerating the slave trade until 1808 and otherwise

silent on the question of human bondage) was a document

inconsistent with the ideals of American liberty, and he

waged a brutal civil war to amend the constitution.

An unintended consequence of that war, however, which

broke the power of individual states to operate farms as

prison labor camps, was to concentrate in Washington and

in the office of the presidency a host of powers (over

the budget and the military, especially) that the

founding fathers had never intended to confer on one

person.

I am not blaming Lincoln alone for the rise of the

imperious presidency. Many others—Woodrow Wilson

included—can share that poisoned chalice.

In particular, American wars (from Mexico in 1846

through to Iraq and Afghanistan) have remade the

presidency into what it is today, a caricature of

democracy dressed up in the raiments of a mail-order

autocrat.

***

When it came to defining the presidency, the

constitution got more wrong than it did right.

The vote wasn’t given to the citizenry but to

electors, wise men in the provinces who would gather (in

early December) every four years and pick a president.

(Golf club membership committees work the same way.) But

the way electors have been chosen over time has been a

political variation of blind man’s buff.

What went wrong almost immediately were the so-called

presidential elections, which since 1792 have been

rigged, fixed, finagled, gerrymandered, massaged,

bought, and sold—yet another cornered commodity market,

although this one trading only in political influence.

Despite what you read about democracy-in-action in

your high school civics classes, most accessions to

presidential power have come as a result of a deal,

bullets, blackmail, or fatal illnesses.

Yet this is the ritual held up to the rest of world,

when someone in Washington is delivering one of those

hectoring speeches about American exceptionalism.

Only in a handful of presidential elections has a

candidate actually taken office after securing more than

50 percent of the votes cast.

Even in the last election, Hillary Clinton won the

popular vote by 2.8 million but Trump was installed in

office, for corralling more electoral votes.

Here’s a short list of brokered, anointed,

non-elected, or somehow accidental American presidents:

George Washington, Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, John

Tyler, Andrew Johnson, Rutherford B. Hayes, Theodore

Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Harry Truman, Lyndon

Johnson, Gerald Ford, and George W. Bush.

Mind you, not all of these presidents were bad. As

was said of Hayes: “He did such a good job I almost wish

he had been elected.”

And here’s a list of some presidents who took office

by the grace of providence or its fix-it men: Abraham

Lincoln (four candidates were running and he got only

39.8% of the vote), Benjamin Harrison (Cleveland won the

popular vote in 1888), William McKinley (Mark Hanna sold

him in 1896 as if he were a new line of soap and then

bought some extra votes, just to be sure), John F.

Kennedy (dead men voting in Mayor Richard J. Daley’s

Cook County), Bill Clinton (he can thank Ross Perot),

and Donald Trump (he lost the popular vote but won the

Russian caucus).

My point is that the words “American democracy” and “

the presidency” have very little in common. Most

elections in U.S. history are variations on the Supreme

Court in 2000 giving the job to George W. Bush much as

he was tapped at Yale for Skull and Bones.

Unless I miss my mark, 2020 will be a rerun of many

earlier contested elections, with voter suppression,

lost and shredded ballots, foreign interference, broken

voting machines, absent absentee ballots, and hacked

computers defining a dubious outcome.

***

How then to remake the presidency so that the office

adds up to something more than a cereal-box kingdom?

Adopting Franklin’s and Jefferson’s Swiss federal

council model might go a long way toward restoring trust

in government, and it would work as follows.

Instead of the president being one person, the chief

executive of the country would be a duly constituted

collective body—say of seven individuals—that as a group

would share the burdens and responsibilities of the

highest office.

In Switzerland (where I live), while there is a

person with the ceremonial title of president, it is

only the Federal Council as a body that can make

executive decisions.

Does it work? Swiss democracy and its Federal Charter

have been around since 1291, so something about the

consensus of a council at the head of government must

function well.

More applicable to the United States: in 1848 the

Swiss adopted a constitution largely based on the

American model; the only exception is that they made the

chief executive a committee, not one person.

The Federal Assembly—both branches of the Swiss

parliament—elects the members of the Federal Council

every four years in December. (If that sounds familiar,

it should. The Federal Assembly is the electoral college

of the Swiss system.)

Generally in Switzerland the federal council is a

blend of the left, right, and center, and it also has

geographic diversity.

Nor does Switzerland tear itself apart every four

years with a presidential election that costs more than

$1 billion and only gives the illusion of

self-government.

Instead, Swiss voters cast about thirty to forty

votes a year (in person, by mail, or on the internet,

and it all works seamlessly; no one stands in eight-hour

lines), on a host of questions, initiatives, and

referenda. Every Swiss citizen, in effect, is a

parliamentarian.

Only periodically do Swiss voters choose actual

candidates; most of the time they are supporting one of

the country’s many political parties or voting yes/no on

specific questions.

The advantage of a federal council in the United

States is that it would introduce into the government a

coalition executive that would make decisions consistent

with the views of the major political parties and hence

(we hope) the electorate at large.

And the idea would be faithful to the original intent

of the U.S. Constitution—that of having electors decide

on the chief executive.

***

During 2020 I was thinking about a federal council

when I followed the presidential campaign trails through

Iowa and New Hampshire.

Over several weeks, I saw all of the candidates in

person (including the carnival-barking Trump at one of

his rallies), and I listened to most of them give more

than one speech or interview.

Listening to the candidates speak, I found few of

them (Biden in particular) to be persuasive as

individuals, but it was easy to imagine that some of the

candidates could be stronger if brought together as

members of a governing body.

So here’s my federal council from the candidates in

the 2020 election:

In no particular order, the most articulate

candidates that I heard in 2020 were Bernie Sanders,

Elizabeth Warren, William Weld (he ran against Trump in

the Republican primaries), Deval Patrick (former

governor of Massachusetts), Amy Klobuchar, Pete

Buttigieg, and Joe Walsh (a Republican – Libertarian

former Congressman who also opposed Trump).

Could those seven persons run the executive branch of

the United States? I think they could. They would

represent the left, right, and center; they would have

ethnic and gender diversity; and they would speak for a

wide variety of constituencies within the country. Plus

there would be collective strength in numbers.

On his own as president Bernie Sanders might be

little more than a left-wing version of Donald Trump,

someone given to sweeping pronouncements (although in a

more dignified manner and without the company of porn

stars).

On a federal council, however, Bernie’s passion for

social justice, education, climate initiatives, and a

limited foreign policy might even find allies among

conservatives Weld and Walsh, provided he was willing to

compromise on monetary and fiscal restraints.

So too would a council be the obvious instrument to

rein in some of Warren’s exuberance and professorial

hectoring, but still allow her to bring to the

government her commitment to economic fairness and

health-care reform.

Buttigieg, Klobuchar, and Patrick are centrists who

speak well for various constituencies, and all three

would be valuable team members.

The way the council operates in Switzerland is that

each member is responsible for certain ministries

(education, foreign affairs, treasury, etc.) for a

year’s term, and then they rotate jobs (including that

of president), which means that council members become

well-versed in various government issues.

For what it’s worth, in Switzerland Covid infections

are down to about ten new cases a day, and there are

only 18 persons with the virus in intensive care around

the country, although in the early days infection rates

were similar to those of the United States.

Yes, nominally, there is a Swiss president (in recent

years very often a woman—there have been six in the

country’s recent history), who is trotted out to meet

world leaders and to represent Switzerland at forums.

But executive authority rests in collective decision. On

her or his own, the Swiss president cannot do very much.

***

For a variety of reasons most recent American

presidencies have ended in failure. Lyndon Johnson

saddled the country with the Vietnam War. Nixon went

down over Watergate, clearly nothing a committee would

have tolerated.

Carter, although a decent man, was over his head with

inflation and Iran, and could have used some adults

(more than Jody and Ham) in the room. Reagan was a

part-time president and had little interest in the

details of government, other than to pay off his friends

and large companies.

George Herbert Walker Bush, in effect, served

Reagan’s third term but found himself squeezed from the

left and right, not to mention by his own incompetence.

Clinton’s personal failings would have mattered less if

he had been one of seven governing the executive branch.

Both George W. Bush and Obama were symbolic

presidents, each representing some lost ideal of their

parties, but neither had much to offer in terms of

management capability, and each blundered into ruinous

foreign wars.

On his own as the American chief executive, the

narcissistic sociopath Trump is a train wreck, for the

presidency and the country. Even if elected, Biden will

be a lame, if not a dead, duck, his presidency over

before it starts.

Do we need more examples, especially during a

financial and health crisis, that the office is failing

us?

I cannot promise that a presidential federal council

would not make mistakes, but at least such a body would

be aligned with the parties and political interests in

the House and Senate, and most Americans would feel that

there was at least someone at the executive level who

was speaking for their interests. (Look through the list

of my federal council, and you will find someone on it

you admire and respect.)

Yes, for a council to succeed it needs compromise,

but think of all the committees in your life that, on

balance, function well. They exchange ideas, barter

favors, and in the end move forward, generally for the

common good. At least most of them don’t storm off in a

cloud of tear gas across Lafayette Square, waving a

Bible.

If you are interested to figure out where you fit

on the Swiss political spectrum, go to

SmartVote and answer the questions.

Matthew Stevenson is the author

of many books, including

Reading the Rails and, most recently,

Appalachia Spring, about the coal counties of

West Virginia and Kentucky. He lives in Switzerland.

- "Source"

-

Post your comment below