By Michael Hudson

In the latest

It’s Our Money podcast,

PBI Chair Ellen Brown and co-host Walt McRee

speak with renowned economist Michael

Hudson, member of the Public Banking

Institute Advisory Board. Walt introduces

the episode:

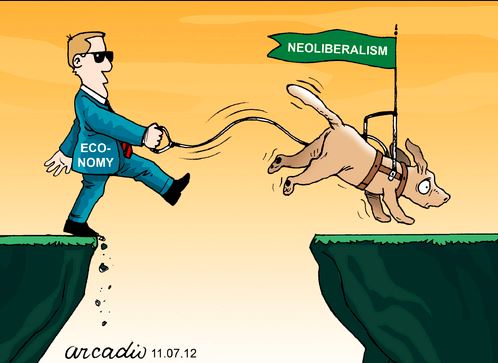

The global economic

devastation produced by market-driven

profiteering has resulted in distressed and

deprived citizens taking to the streets by

the hundreds of thousands in cities around

the globe and continues its destructive

exploitation of our planet’s resources. The

culprit is an aging “neo-liberal” economic

system which produces historic social

inequality while consolidating power in the

hands of a few. Our guest, renowned

economist Michael Hudson, says this system

is more neo-feudal than neo-liberal – and

that its inherent excesses are on

the verge of bringing it down.

Ellen reports that one example of its demise

may be in Mexico where its new president is

creating new public banks to help address

some of its neo-liberal market inequities. -

[Listen

to the podcast]

Michael Hudson: [00:00:00] There’s recognition

that commercial banking has become dysfunctional and

that most loans by commercial banks are either

against assets – in which case the lending inflates

the prices of real estate, stocks and bonds – or for

corporate takeover loans.

The economy’s low-income brackets have not been

helped by today’s financial system. Here in New York

City, red lining and a visceral class hatred by high

finance toward the poor characterized the major

banks. From the very top to the bottom, they were

very clear they were not going to lend to places

with racial minorities like the Lower East Side. The

Chase Manhattan Bank told me that the reason was

explicitly ethnic, and they didn’t want to deal with

poor people.

A lot of people in these neighborhoods used to

have savings banks. There were 135 mutual savings

banks in New York City with names like the Bowery

Savings Banks, the Dime Savings Bank, the Immigrant

Savings Bank. As their names show, they were

specifically to serve the low-income neighborhoods.

But in the 1980s the commercial banks convinced the

mutual savings banks to let themselves be raided.

Their capital reserves of the savings banks, was

just looted by Wall Street. The depositors’ equity

was stripped away (leaving their deposits, to be

sure). Sheila Bair, former head of the FDIC, told me

that the commercial banks’ cover story was that they

were large enough to provide more capital reserves

to lend for low-income neighborhoods. The reality

was that instead, they simply extracted revenue from

these neighborhoods. Large parts of the largest

cities in America, from Chicago and New York to

others, are underbanked because of the

transformation of commercial banks from providers of

mortgages to emptiers-out, just revenue collectors.

That leaves the main recourse in these neighborhoods

to pay-day lenders at usurious interest rates. These

lenders have become major new customers for Wall

Street bankers, not the poor who have no comparable

access to credit.

Apart from the savings banks, of course, you had

the post office banks. When I went to work on Wall

Street in the 1960s, 3 percent of U.S. savings were

in the form of post office savings. The advantage,

of course, is that post offices were in every

neighborhood. So you actually had either a local

community banking like savings banks – not like

today’s community banks, which are commercial banks,

lending largely to real estate speculators to

capitalize rental apartments into heavily mortgaged

co-ops with much higher financial carrying charges –

or you had post offices. You now have a deprivation

of basic bank services in much of the economy,

combined with an increasingly dysfunctional and

predatory commercial banking system.

The question is, what’s going to happen next time

there’s a bank crash? Sheila Bair wrote about after

the 2008 crash that the most corrupt bank was

Citibank – not only corrupt, but incompetent. She

had wanted to take it over. But Obama and his

Secretary of the Treasury, Tim Geithner, acted as

lobbyists for Citibank from the beginning,

protecting it from being taken over. But imagine

what would have happened if Citibank would have been

become a public bank – or other banks that are about

to have negative equity if there is a downturn in

the stock and bond and real estate market. Imagine

what will happen if they were turned into public

banks. They would be able to provide the kind of

credit that the commercial banking system has

refused to provide – credit to blacks, Hispanics and

poor people that have just been red-lined in what is

becoming a financially polarized dual economy, one

for the wealthy and one for everyone else.