By Craig Murray

February 27, 2020 "Information

Clearing House" - In yesterday’s

proceedings in court, the prosecution adopted

arguments so stark and apparently unreasonable I

have been fretting on how to write them up in a way

that does not seem like caricature or unfair

exaggeration on my part. What has been happening in

this court has long moved beyond caricature. All I

can do is give you my personal assurance that what I

recount actually is what happened.

As usual, I shall deal with procedural matters

and Julian’s treatment first, before getting in to a

clear account of the legal arguments made.

Vanessa Baraitser is under a clear instruction to

mimic concern by asking, near the end of every

session just before we break anyway, if Julian is

feeling well and whether he would like a break. She

then routinely ignores his response. Yesterday he

replied at some length he could not hear properly in

his glass box and could not communicate with his

lawyers (at some point yesterday they had started

preventing him passing notes to his counsel, which I

learn was the background to the aggressive

prevention of his shaking Garzon’s hand goodbye).

Baraitser insisted he might only be heard through

his counsel, which given he was prevented from

instructing them was a bit rich. This being pointed

out, we had a ten minute adjournment while Julian

and his counsel were allowed to talk down in the

cells – presumably where they could be more

conveniently bugged yet again.

On return, Edward Fitzgerald made a formal

application for Julian to be allowed to sit beside

his lawyers in the court. Julian was “a gentle,

intellectual man” and not a terrorist. Baraitser

replied that releasing Assange from the dock into

the body of the court would mean he was released

from custody. To achieve that would require an

application for bail.

Again, the prosecution counsel James Lewis

intervened on the side of the defence to try to make

Julian’s treatment less extreme. He was not, he

suggested diffidently, quite sure that it was

correct that it required bail for Julian to be in

the body of the court, or that being in the body of

the court accompanied by security officers meant

that a prisoner was no longer in custody.

|

Are You Tired Of

The Lies And

Non-Stop Propaganda?

|

Prisoners, even the most dangerous of

terrorists, gave evidence from the

witness box in the body of the court

nest to the lawyers and magistrate. In

the High Court prisoners frequently sat

with their lawyers in extradition

hearings, in extreme cases of violent

criminals handcuffed to a security

officer.

Baraitser replied that Assange might pose a

danger to the public. It was a question of health

and safety. How did Fitzgerald and Lewis think that

she had the ability to carry out the necessary risk

assessment? It would have to be up to Group 4 to

decide if this was possible.

Yes, she really did say that. Group 4 would have

to decide.

Baraitser started to throw out jargon like a

Dalek when it spins out of control. “Risk

assessment” and “health and safety” featured a lot.

She started to resemble something worse than a Dalek,

a particularly stupid local government officer of a

very low grade. “No jurisdiction” – “Up to Group 4”.

Recovering slightly, she stated firmly that delivery

to custody can only mean delivery to the dock of the

court, nowhere else in the room. If the defence

wanted him in the courtroom where he could hear

proceedings better, they could only apply for bail

and his release from custody in general. She then

peered at both barristers in the hope this would

have sat them down, but both were still on their

feet.

In his diffident manner (which I confess is

growing on me) Lewis said “the prosecution is

neutral on this request, of course but, err, I

really don’t think that’s right”. He looked at her

like a kindly uncle whose favourite niece has just

started drinking tequila from the bottle at a family

party.

Baraitser concluded the matter by stating that

the Defence should submit written arguments by 10am

tomorrow on this point, and she would then hold a

separate hearing into the question of Julian’s

position in the court.

The day had begun with a very angry Magistrate

Baraitser addressing the public gallery. Yesterday,

she said, a photo had been taken inside the

courtroom. It was a criminal offence to take or

attempt to take photographs inside the courtroom.

Vanessa Baraitser looked at this point very keen to

lock someone up. She also seemed in her anger to be

making the unfounded assumption that whoever took

the photo from the public gallery on Tuesday was

still there on Wednesday; I suspect not. Being angry

at the public at random must be very stressful for

her. I suspect she shouts a lot on trains.

Ms Baraitser is not fond of photography – she

appears to be the only public figure in Western

Europe with no photo on the internet. Indeed the

average proprietor of a rural car wash has left more

evidence of their existence and life history on the

internet than Vanessa Baraitser. Which is no crime

on her part, but I suspect the expunging is not

achieved without considerable effort. Somebody

suggested to me she might be a hologram, but I think

not. Holograms have more empathy.

I was amused by the criminal offence of

attempting to take photos in the courtroom. How

incompetent would you need to be to attempt to take

a photo and fail to do so? And if no photo was

taken, how do they prove you were attempting to take

one, as opposed to texting your mum? I suppose

“attempting to take a photo” is a crime that could

catch somebody arriving with a large SLR, tripod and

several mounted lighting boxes, but none of those

appeared to have made it into the public gallery.

Baraitser did not state whether it was a criminal

offence to publish a photograph taken in a courtroom

(or indeed to attempt to publish a photograph taken

in a courtroom). I suspect it is. Anyway Le

Grand Soir has published

a translation of my report yesterday, and there

you can see a photo of Julian in his bulletproof

glass anti-terrorist cage. Not, I hasten to add,

taken by me.

We now come to the consideration of yesterday’s

legal arguments on the extradition request itself.

Fortunately, these are basically fairly simple to

summarise, because although we had five hours of

legal disquisition, it largely consisted of both

sides competing in citing scores of “authorities”,

e.g. dead judges, to endorse their point of view,

and thus repeating the same points continually with

little value from exegesis of the innumerable

quotes.

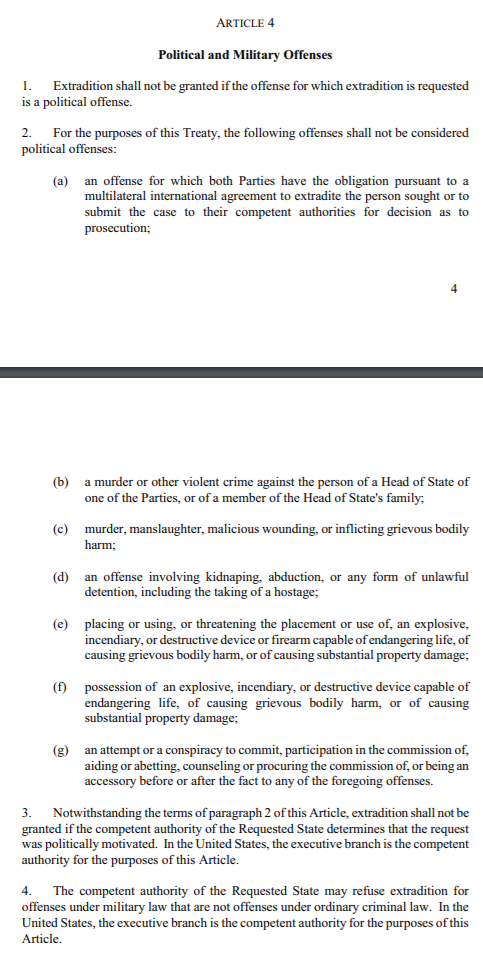

As prefigured yesterday by magistrate Baraitser,

the prosecution is arguing that Article 4.1 of the

UK/US extradition treaty has no force in law.

The UK and US Governments say that the court

enforces domestic law, not international law, and

therefore the treaty has no standing. This argument

has been made to the court in written form to which

I do not have access. But from discussion in court

it was plain that the prosecution argue that the

Extradition Act of 2003, under which the court is

operating, makes no exception for political

offences. All previous Extradition Acts had excluded

extradition for political offences, so it must be

the intention of the sovereign parliament that

political offenders can now be extradited.

Opening his argument, Edward Fitzgerald QC argued

that the Extradition Act of 2003 alone is not enough

to make an actual extradition. The extradition

requires two things in place; the general

Extradition Act and the Extradition Treaty with the

country or countries concerned. “No Treaty, No

Extradition” was an unbreakable rule. The Treaty was

the very basis of the request. So to say that the

extradition was not governed by the terms of the

very treaty under which it was made, was to create a

legal absurdity and thus an abuse of process. He

cited examples of judgements made by the House of

Lords and Privy Council where treaty rights were

deemed enforceable despite the lack of incorporation

into domestic legislation, particularly in order to

stop people being extradited to potential execution

from British colonies.

Fitzgerald pointed out that while the Extradition

Act of 2003 did not contain a bar on extraditions

for political offences, it did not state there could

not be such a bar in extradition treaties. And the

extradition treaty of 2007 was ratified after the

2003 extradition act.

At this stage Baraitser interrupted that it was

plain the intention of parliament was that there

could be extradition for political offences.

Otherwise they would not have removed the bar in

previous legislation. Fitzgerald declined to agree,

saying the Act did not say extradition for political

offences could not be banned by the treaty enabling

extradition.

Fitzgerald then continued to say that

international jurisprudence had accepted for a

century or more that you did not extradite political

offenders. No political extradition was in the

European Convention on Extradition, the Model United

Nations Extradition Treaty and the Interpol

Convention on Extradition. It was in every single

one of the United States’ extradition treaties with

other countries, and had been for over a century, at

the insistence of the United States. For both the UK

and US Governments to say it did not apply was

astonishing and would set a terrible precedent that

would endanger dissidents and potential political

prisoners from China, Russia and regimes all over

the world who had escaped to third countries.

Fitzgerald stated that all major authorities

agreed there were two types of political offence.

The pure political offence and the relative

political offence. A “pure” political offence was

defined as treason, espionage or sedition. A

“relative” political offence was an act which was

normally criminal, like assault or vandalism,

conducted with a political motive. Every one of the

charges against Assange was a “pure” political

offence. All but one were espionage charges, and the

computer misuse charge had been compared by the

prosecution to breach of the official secrets act to

meet the dual criminality test. The overriding

accusation that Assange was seeking to harm the

political and military interests of the United

States was in the very definition of a political

offence in all the authorities.

In reply Lewis stated that a treaty could not be

binding in English law unless specifically

incorporated in English law by Parliament. This was

a necessary democratic defence. Treaties were made

by the executive which could not make law. This went

to the sovereignty of Parliament. Lewis quoted many

judgements stating that international treaties

signed and ratified by the UK could not be enforced

in British courts. “It may come as a surprise to

other countries that their treaties with the British

government can have no legal force” he joked.

Lewis said there was no abuse of process here and

thus no rights were invoked under the European

Convention. It was just the normal operation of the

law that the treaty provision on no extradition for

political offences had no legal standing.

Lewis said that the US government disputes that

Assange’s offences are political. In the

UK/Australia/US there was a different definition of

political offence to the rest of the world. We

viewed the “pure” political offences of treason,

espionage and sedition as not political offences.

Only “relative” political offences – ordinary crimes

committed with a political motive – were viewed as

political offences in our tradition. In this

tradition, the definition of “political” was also

limited to supporting a contending political party

in a state. Lewis will continue with this argument

tomorrow.

That concludes my account of proceedings. I have

some important commentary to make on this and will

try to do another posting later today. Now rushing

to court.

With grateful thanks to those who donated or

subscribed to make this reporting possible.

This article is entirely free to reproduce and

publish, including in translation, and I very much

hope people will do so actively. Truth shall set us

free.

Craig's blog has no source of state, corporate

or institutional finance whatsoever. Support

Craig's work

https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/support-this-website/

Do you agree or disagree? Post

your comment here

Assanage Show Trial: Your Man in the Public

Gallery – The Assange Hearing Day 3

By Craig Murray

February 27, 2020 "Information

Clearing House" - Please try this

experiment for me.

Try asking this question out loud, in a tone of

intellectual interest and engagement: “Are you

suggesting that the two have the same effect?”.

Now try asking this question out loud, in a tone

of hostility and incredulity bordering on sarcasm:

“Are you suggesting that the two have the same

effect?”.

Firstly, congratulations on your acting skills;

you take direction very well. Secondly, is it not

fascinating how precisely the same words can convey

the opposite meaning dependent on modulation of

stress, pitch, and volume?

Yesterday the prosecution continued its argument

that the provision in the 2007 UK/US Extradition

Treaty that bars extradition for political offences

is a dead letter, and that Julian Assange’s

objectives are not political in any event. James

Lewis QC for the prosecution spoke for about an

hour, and Edward Fitzgerald QC replied for the

defence for about the same time. During Lewis’s

presentation, he was interrupted by Judge Baraitser

precisely once. During Fitzgerald’s reply, Baraitser

interjected seventeen times.

In the transcript, those interruptions will not

look unreasonable:

“Could you clarify that for me Mr Fitzgerald…”

“So how do you cope with Mr Lewis’s point that…”

“But surely that’s a circular argument…”

“But it’s not incorporated, is it?…”

All these and the other dozen interruptions were

designed to appear to show the judge attempting to

clarify the defence’s argument in a spirit of

intellectual testing. But if you heard the tone of

Baraitser’s voice, saw her body language and facial

expressions, it was anything but.

The false picture a transcript might give is

exacerbated by the courtly Fitzgerald’s continually

replying to each obvious harassment with “Thank you

Madam, that is very helpful”, which again if you

were there, plainly meant the opposite. But what a

transcript will helpfully nevertheless show was the

bully pulpit of Baraitser’s tactic in interrupting

Fitzgerald again and again and again, belittling his

points and very deliberately indeed preventing him

from getting into the flow of his argument. The

contrast in every way with her treatment of Lewis

could not be more pronounced.

So now to report the legal arguments themselves.

James Lewis for the prosecution, continuing his

arguments from the day before, said that Parliament

had not included a bar on extradition for political

offences in the 2003 Act. It could therefore not be

reintroduced into law by a treaty. “To introduce a

Political Offences bar by the back door would be to

subvert the intention of Parliament.”

Lewis also argued that these were not political

offences. The definition of a political offence was

in the UK limited to behaviour intended “to overturn

or change a government or induce it to change its

policy.” Furthermore the aim must be to change

government or policy in the short term, not the

indeterminate future.

Lewis stated that further the term “political

offence” could only be applied to offences committed

within the territory where it was attempted to make

the change. So to be classified as political

offences, Assange would have had to commit them

within the territory of the USA, but he did not.

If Baraitser did decide the bar on political

offences applied, the court would have to determine

the meaning of “political offence” in the UK/US

Extradition Treaty and construe the meaning of

paragraphs 4.1 and 4.2 of the Treaty. To construe

the terms of an international treaty was beyond the

powers of the court.

Lewis perorated that the conduct of Julian

Assange cannot possibly be classified as a political

offence. “It is impossible to place Julian Assange

in the position of a political refugee”. The

activity in which Wikileaks was engaged was not in

its proper meaning political opposition to the US

Administration or an attempt to overthrow that

administration. Therefore the offence was not

political.

For the defence Edward Fitzgerald replied that

the 2003 Extradition Act was an enabling act under

which treaties could operate. Parliament had been

concerned to remove any threat of abuse of the

political offence bar to cover terrorist acts of

violence against innocent civilians. But there

remained a clear protection, accepted worldwide, for

peaceful political dissent. This was reflected in

the Extradition Treaty on the basis of which the

court was acting.

Baraitser interrupted that the UK/US Extradition

Treaty was not incorporated into English Law.

Fitzgerald replied that the entire extradition

request is on the basis of the treaty. It is an

abuse of process for the authorities to rely on the

treaty for the application but then to claim that

its provisions do not apply.

“On the face of it, it is a very bizarre

argument that a treaty which gives rise to the

extradition, on which the extradition is

founded, can be disregarded in its provisions.

It is on the face of it absurd.” Edward

Fitzgerald QC for the Defence

Fitzgerald added that English Courts construe

treaties all the time. He gave examples.

Fitzgerald went on that the defence did not

accept that treason, espionage and sedition were not

regarded as political offences in England. But even

if one did accept Lewis’s too narrow definition of

political offence, Assange’s behaviour still met the

test. What on earth could be the motive of

publishing evidence of government war crimes and

corruption, other than to change the policy of the

government? Indeed, the evidence would prove that

Wikileaks had effectively changed the policy of the

US government, particularly on Iraq.

Baraitser interjected that to expose government

wrongdoing was not the same thing as to try to

change government policy. Fitzgerald asked her,

finally in some exasperation after umpteen

interruptions, what other point could there be in

exposing government wrongdoing other than to induce

a change in government policy?

That concluded opening arguments for the

prosecution and defence.

MY PERSONAL COMMENTARY

Let me put this as neutrally as possible. If you

could fairly state that Lewis’s argument was much

more logical, rational and intuitive than

Fitzgerald’s, you could understand why Lewis did not

need an interruption while Fitzgerald had to be

continually interrupted for “clarification”. But in

fact it was Lewis who was making out the case that

the provisions of the very treaty under which the

extradition is being made, do not in fact apply, a

logical step which I suggest the man on the Clapham

omnibus might reason to need rather more testing

than Fitzgerald’s assertion to the contrary.

Baraitser’s comparative harassment of Fitzgerald

when he had the prosecution on the ropes was

straight out of the Stalin show trial playbook.

The defence did not mention it, and I do not know

if it features in their written arguments, but I

thought Lewis’s point that these could not be

political offences, because Julian Assange was not

in the USA when he committed them, was

breathtakingly dishonest. The USA claims universal

jurisdiction. Assange is being charged with crimes

of publishing committed while he was outside the

USA. The USA claims the right to charge anyone of

any nationality, anywhere in the world, who harms US

interests. They also in addition here claim that as

the materials could be seen on the internet in the

USA, there was an offence in the USA. At the same

time to claim this could not be a political offence

as the crime was committed outside the USA is, as

Edward Fitzgerald might say, on the face of it

absurd. Which curiously Baraitser did not pick up

on.

Lewis’s argument that the Treaty does not have

any standing in English law is not something he just

made up. Nigel Farage did not materialise from

nowhere. There is in truth a long tradition in

English law that even a treaty signed and ratified

with some bloody Johnny Foreigner country, can in no

way bind an English court. Lewis could and did spout

reams and reams of judgements from old beetroot

faced judges holding forth to say exactly that in

the House of Lords, before going off to shoot grouse

and spank the footman’s son. Lewis was especially

fond of the Tin Council

case.

There is of course a contrary and more

enlightened tradition, and a number of judgements

that say the exact opposite, mostly more recent.

This is why there was so much repetitive argument as

each side piled up more and more volumes of

“authorities” on their side of the case.

The difficulty for Lewis – and for Baraitser – is

that this case is not analogous to me buying a Mars

bar and then going to court because an International

Treaty on Mars Bars says mine is too small.

Rather the 2003 Extradition Act is an Enabling

Act on which extradition treaties then depend. You

can’t thus extradite under the 2003 Act without the

Treaty. So the Extradition Treaty of 2007 in a very

real sense becomes an executive instrument legally

required to authorise the extradition. For the

executing authorities to breach the terms of the

necessary executive instrument under which they are

acting, simply has to be an abuse of process. So the

Extradition Treaty owing to its type and its

necessity for legal action, is in fact incorporated

in English Law by the Extradition Act of 2003 on

which it depends.

The Extradition Treaty is a necessary

precondition of the extradition, whereas a Mars Bar

Treaty is not a necessary precondition to buying the

Mars Bar.

That is as plain as I can put it. I do hope that

is comprehensible.

It is of course difficult for Lewis that on the

same day the Court of Appeal was ruling against the

construction of the Heathrow Third Runway, partly

because of its incompatibility with the Paris

Agreement of 2016, despite the latter not being

fully incorporated into English law by the Climate

Change Act of 2008.

VITAL PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

It is intensely embarrassing for the Foreign and

Commonwealth Office (FCO) when an English court

repudiates the application of a treaty the UK has

ratified with one or more foreign states. For that

reason, in the modern world, very serious procedures

and precautions have been put into place to make

certain that this cannot happen. Therefore the

prosecution’s argument that all the provisions of

the UK/US Extradition Treaty of 2007 are not able to

be implemented under the Extradition Act of 2003,

ought to be impossible.

I need to explain I have myself negotiated and

overseen the entry into force of treaties within the

FCO. The last one in which I personally tied the

ribbon and applied the sealing wax (literally) was

the Anglo-Belgian Continental Shelf Treaty of 1991,

but I was involved in negotiating others and the

system I am going to describe was still in place

when I left the FCO as an Ambassador in 2005, and I

believe is unchanged today (and remember the

Extradition Act was 2003 and the US/UK Extradition

Treaty ratified 2007, so my knowledge is not

outdated). Departmental nomenclatures change from

time to time and so does structural organisation.

But the offices and functions I will describe

remain, even if names may be different.

All international treaties have a two stage

process. First they are signed to show the

government agrees to the treaty. Then, after a

delay, they are ratified. This second stage takes

place when the government has enabled the

legislation and other required agency to implement

the treaty. This is the answer to Lewis’s

observation about the roles of the executive and

legislature. The ratification stage only takes place

after any required legislative action. That is the

whole point.

This is how it happens in the FCO. Officials

negotiate the extradition treaty. It is signed for

the UK. The signed treaty then gets returned to FCO

Legal Advisers, Nationality and Treaty Department,

Consular Department, North American Department and

others and is sent on to Treasury/Cabinet Office

Solicitors and to Home Office, Parliament and to any

other Government Department whose area is impacted

by the individual treaty.

The Treaty is extensively vetted to check that it

can be fully implemented in all the jurisdictions of

the UK. If it cannot, then amendments to the law

have to be made so that it can. These amendments can

be made by Act of Parliament or more generally by

secondary legislation using powers conferred on the

Secretary of State by an act. If there is already an

Act of Parliament under which the Treaty can be

implemented, then no enabling legislation needs to

be passed. International Agreements are not

all individually incorporated into English or

Scottish laws by specific new legislation.

This is a very careful step by step process,

carried out by lawyers and officials in the FCO,

Treasury, Cabinet Office, Home Office, Parliament

and elsewhere. Each will in parallel look at every

clause of the Treaty and check that it can be

applied. All changes needed to give effect to the

treaty then have to be made – amending legislation,

and necessary administrative steps. Only when all

hurdles have been cleared, including legislation,

and Parliamentary officials, Treasury, Cabinet

Office, Home Office and FCO all certify that the

Treaty is capable of having effect in the UK, will

the FCO Legal Advisers give the go ahead for the

Treaty to be ratified. You absolutely cannot

ratify the treaty before FCO Legal Advisers have

given this clearance.

This is a serious process. That is why the US/UK

Extradition Treaty was signed in 2003 and ratified

in 2007. That is not an abnormal delay.

So I know for certain that ALL the relevant

British Government legal departments MUST have

agreed that Article 4.1 of the UK/US Extradition

Treaty was capable of being given effect under the

2003 Extradition Act. That certification has to have

happened or the Treaty could never have been

ratified.

It follows of necessity that the UK Government,

in seeking to argue now that Article 4.1 is

incompatible with the 2003 Act, is knowingly lying.

There could not be a more gross abuse of process.

I have been keen for the hearing on this

particular point to conclude so that I could give

you the benefit of my experience. I shall rest there

for now, but later today hope to post further on

yesterday’s row in court over releasing Julian from

the anti-terrorist armoured dock.

With grateful thanks to those who donated or

subscribed to make this reporting possible. I wish

to stress again that I absolutely do not want

anybody to give anything if it causes them the

slightest possibility of financial strain.

This article is entirely free to reproduce and

publish, including in translation, and I very much

hope people will do so actively. Truth shall set us

free.

Craig's blog has no source of state, corporate

or institutional finance whatsoever. Support

Craig's work

https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/support-this-website/

Do you agree or disagree? Post

your comment here

| |