Bolivia coup plotters

dismissed the elections as fraudulent. Our

research found no reason to suspect fraud.

Bolivians will hold a new election in May —

without ousted president Evo Morales

By John Curiel and Jack R. Williams

Feb. 27, 2020 at

12:45 p.m. UTC -

As

Bolivia gears up for a

do-over election

on May 3, the country remains in

unrest following the Nov. 10

military-backed coup against

incumbent President Evo Morales.

A quick

recap: Morales claimed victory in

October’s election, but the

opposition protested about what it

called

electoral fraud.

A Nov. 10

report

from the

Organization of American States

(OAS) noted election irregularities,

which “leads the technical audit

team to question the integrity of

the results of the election on

October 20.” Police then joined the

protests and Morales sought asylum

in Mexico.

The

military-installed government

charged Morales with sedition and

terrorism. A European Union

monitoring report noted that some

40 former electoral officials

have been arrested and face criminal

charges of

sedition and subversion,

and

35 people have died

in the post-electoral conflict. The

highest-polling presidential

candidate, a member of Morales’s

Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS-IPSP)

party, has received a summons from

prosecutors for undisclosed crimes,

a move some analysts suspect was

aimed to

keep him off the ballot.

The OAS claimed that

election fraud had happened

The primary support for

claims of fraud was the

OAS report.

The organization’s auditors

claimed to have found

evidence of fraud following

a halt in the preliminary

count — the nonbinding

election-night results meant

to track progress before the

official count.

The Bolivian constitution

requires that a candidate

either earn an outright

electoral majority or 40

percent of the votes, with

at least a

10-percentage-point lead.

Otherwise, a runoff election

will take place. The

preliminary count halted

with 84 percent of the vote

counted, when Morales had a

7.87 percentage-point lead.

Though the halt was

consistent with election

officials’ earlier

promise to count at least 80

percent

of the preliminary vote on

election night and continue

through the official count,

the OAS quickly expressed

concern over the stop. When

the preliminary count

resumed, Morales’s margin

was above the

10-percentage-point

threshold.

The OAS claimed that halting

the preliminary count

resulted in a “highly

unlikely” trend in the

margin in favor of MAS-IPSP

when the count resumed. The

OAS reported “deep

concern

and surprise at the drastic

and hard-to-explain change

in the trend of the

preliminary results.”

Adopting a novel approach to

fraud analysis, the OAS

claimed that high deviations

in data reported before and

after the cutoff would

indicate potential evidence

of fraud.

But the

statistical analysis behind

this claim is problematic

The OAS report is in part

based on forensic evidence

that OAS analysts say points

to irregularities, which

includes allegations of

forged signatures and

alteration of tally sheets,

a deficient chain of

custody, and a halt in the

preliminary vote count.

Crucially, the OAS claimed

in reference to the halt in

the preliminary vote count

that “an irregularity on

that scale is a determining

factor in the outcome” in

favor of Morales, which

acted as the primary

quantitative evidence to

their allegations of “clear

manipulation of the TREP

system … which affected the

results of both that system

and the final count.”

We do not evaluate whether

these irregularities point

to deliberate interference —

or reflect the problems of

an underfunded system with

poorly trained election

officials. Instead, we

comment on the statistical

evidence.

|

Are You Tired Of

The Lies And

Non-Stop Propaganda?

|

Since Morales had surpassed

the 40-percent threshold,

the key question was whether

his vote tally was 10

percentage points higher

than that of his closest

competitor. If not, then

Morales would be forced into

a runoff election against

his closest competitor —

former president Carlos

Mesa.

Our results were

straightforward. There does

not seem to be a

statistically significant

difference in the margin

before and after the halt of

the preliminary vote.

Instead, it is highly likely

that Morales surpassed the

10-percentage-point margin

in the first round.

How did we get there? The

OAS approach relies on dual

assumptions: that the

unofficial count accurately

reflects the vote

continuously measured, and

that reported voter

preferences do not vary by

the time of day. If these

assumptions are true, then a

change in the trend to favor

one party over time could

potentially indicate fraud

had occurred.

The OAS cites no previous

research demonstrating that

these assumptions hold.

There are reasons to believe

that voter preferences and

reporting can vary over

time: with people who work

voting later in the day, for

instance. Areas where

impoverished voters are

clustered may have longer

lines and less ability to

count and report vote totals

quickly. These factors may

well apply in Bolivia, where

there are

severe gaps

in infrastructure and income

between urban and rural

areas.

Was there a discontinuity

between the votes counted

before and after the

unofficial count? For sure,

discontinuities might be

evidence of tampering. In

Russia, for instance, one

allegation is that

local election officials

stuff ballot boxes

to meet preset targets.

If the OAS finding was

correct, we would expect to

see Morales’s vote margin

spike shortly after the

preliminary vote count

halted — and the resulting

election margin over his

closest competitor would be

too large to be explained by

his performance before

preliminary count stopped.

We might expect to see other

anomalies, such as sudden

shifts in votes for Morales

from precincts that were

previously less inclined to

vote for him.

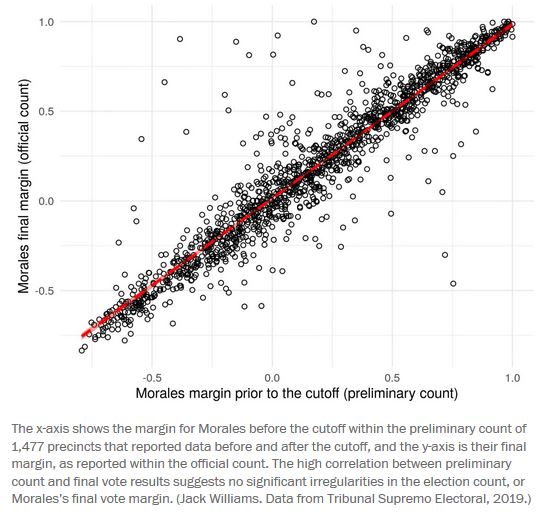

We didn’t find any

evidence of any of these anomalies,

as this figure shows. We find a

0.946 correlation between Morales’s

margin between results before and

after the cutoff in precincts

counted before and after the cutoff.

There is little observable

difference between precincts in the

results before and after the count

halt, suggesting that there weren’t

any significant irregularities. We

and other scholars within the field

reached out to the OAS for comment;

the OAS did not respond.

We also ran 1,000

simulations to see if the

difference between Morales’s

vote and the tally for the

second-place candidate could

be predicted, using only the

votes verified before the

preliminary count halted. In

our simulations, we found

that Morales could expect at

least a 10.49 point lead

over his closest competitor,

above the necessary

10-percentage-point

threshold necessary to win

outright. Again, this

suggests that any increase

in Morales’s margin after

the stop can be explained

entirely by the votes

already counted.

There isn’t statistical

support for the claims of

vote fraud

There is not any statistical

evidence of fraud that we

can find — the trends in the

preliminary count, the lack

of any big jump in support

for Morales after the halt,

and the size of Morales’s

margin all appear

legitimate. All in all, the

OAS’s statistical analysis

and conclusions would appear

deeply flawed.

"Source"

Do you agree

or disagree? Post your comment here

| |

|