January 24, 2020 "Information

Clearing House" -

As part of the bill, Republicans approved

tax breaks in 2017 for seven classes of

assets many of the wealthier members of

Congress held at the time, including

partnerships, small corporations, real

estate, and several esoteric investment

vehicles. While they sold the bill as a

package of business and middle-class tax

cuts that would not help the wealthy,

the cuts likely saved members of

Congress hundreds of thousands of dollars in

taxes collectively, while the corporate tax

cut hiked the value of their holdings.

“It feels to me like a kleptocracy,”

said Jeff Hauser, director of the Revolving Door

Project at the Center for Economic and Policy

Research, a left-leaning think tank in Washington,

DC.

Such congressional self-enrichment

has been thrust into the 2020 presidential campaign.

Democratic candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren has said

her first priority as president would be to pass an

anti-corruption package that, among other things,

would forbid

members of Congress from owning individual

stocks, bonds, and other securities so they could

not benefit from tax or financial laws they passed.

“Under current law, members of

Congress can trade stocks and then use their

powerful positions to increase the value of those

stocks and pad their own pockets,” Warren wrote in a

September

Medium post.

Republicans own lots

of stock

Two years after the passage of the

Trump tax act, its effects — some obvious, some

hidden — are coming into focus. One is its cost:

Contrary to Republican claims, the law is not paying

for itself and is likely to burden the nation with

an additional

$1.9 trillion in debt over 11 years beginning in

2018, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

And while the law cut tax rates for

people of all income brackets, some of its tax

benefits overtly favored the wealthy, such as the

2.6 percentage point tax rate cut in the highest

bracket and the doubling of the estate tax exemption

to $11.2 million. Other provisions were subtler yet

favored the wealthy even more: tax breaks for their

investments, for instance, or changes that boosted

the value of their stocks. Among the rich

beneficiaries are members of Congress, more than

half of whom were found to be millionaires in 2014.

|

Are You Tired Of

The Lies And

Non-Stop Propaganda?

|

The tax law’s centerpiece is its

record cut in the corporate tax rate, from 35

percent to 21 percent. At the time of its passage,

most of the bill’s Republican supporters said the

cut would result in higher wages, factory

expansions, and more jobs. Instead, it was mainly

exploited by corporations, which bought back stock

and raised dividends. In 2018, stock buybacks

exceeded

$1 trillion for the first time ever, according

to TrimTabs, an investment research firm. Net

corporate dividends reached a new high in 2018 of

more than

$1.3 trillion, nearly 6 percent more than the

previous year. The result, analysts say: The

buybacks boosted stock prices, and bigger dividends

put even more money in the pockets of stockholders.

Promises that the tax act would boost

investment have not panned out. Corporate investment

is now at lower levels than before the act passed,

according to the Commerce Department. Though

employment and wages have increased, it is hard to

separate the effect of the tax act from general

economic improvements since the 2008 recession.

The boost in stock prices, however,

was predictable. As the bill was reaching its final

stages in 2017, Bryan Rich, the CEO of Logic Fund

Management, a wealth advisory company,

wrote that the proposed corporate rate cut “will

go right to the bottom line of companies — popping

EPS [earnings per share] and driving stocks even

higher.”

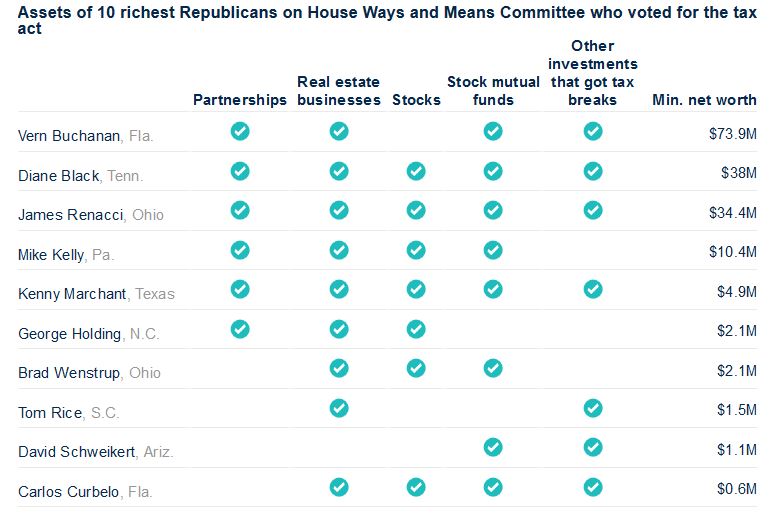

Those benefits mainly went to the

rich, as the wealthiest 10 percent of Americans own

84 percent of all stocks. The 10 richest Republicans

in Congress in 2017 who voted for the tax bill held

more than $731 million in assets, almost two-thirds

of which were in stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and

other instruments, according to Roll Call’s

semiannual assessment of

Congress’s wealth.

The precise amount of

Republicans’ windfall can’t be determined

without a review of the members’ tax

returns, which they are not required to

disclose.

All but one of the 47 Republicans who

sat on the three key committees overseeing the

drafting of the tax bill own stocks and stock mutual

funds, according to Public Integrity’s analysis.

Rep. Mike Kelly (R-PA) was among them. A member of

the Ways and Means Committee, which oversaw the

writing of the tax bill in the House, Kelly reported

in 2018 that his spouse owned 101

individual stocks, Apple included, with a minimum

total value of $439,000.

When he voted for the 2017 tax cuts,

which will be funded by nearly $2 trillion in added

debt, Kelly called it “the most important vote I’ve

ever cast.” Yet 19 months later, he voted against a

two-year budget agreement that

added to the national debt by hiking government

spending for defense and nondefense programs by $320

billion. Kelly warned that “America is driving

toward a fiscal cliff.”

Orrin Hatch (R-UT) was chair of the

Senate Finance Committee in 2017, when he and his

wife owned mutual funds and a limited liability

corporation valued between $562,000 and $1.430

million, paying them between $12,700 and $38,500 in

dividends and capital gains, according to Hatch’s

financial disclosure forms. They also owned a blind

trust worth between $1 million and $5 million.

(Congressional financial disclosure forms do not

require members to report the precise value of

assets and income but rather in 11 different ranges,

each with a minimum and a maximum value.)

For decades, Hatch, who retired in

2018, had been one of the loudest deficit hawks in

Congress. Just 10 months before he would shepherd

the tax bill through his committee, Hatch said, “The

national debt crisis poses a significant and growing

threat to the economic and national security of this

country.”

His concern over national security

lasted two months. In April, Hatch signaled he was

open to a Republican tax bill that would likely add

to the national debt. When Republicans passed the

tax bill in December 2017, he beamed. “This is a

historic night,” he said at a press conference.

(The Center for Public Integrity

sought comment from 13 current or former members of

Congress mentioned in this article; only two

responded.)

A big bump from

overseas onshoring

Republican lawmakers also boosted the

value of their stock holdings when they encouraged

American corporations to repatriate money they were

holding overseas. The tax law decreed that future

foreign profits would not be taxed at high rates,

and that previously earned profits stashed abroad —

an estimated $2.7 trillion — would be taxed one

time at no more than 15.5 percent.

In 2017, Apple was sitting on $250

billion in overseas profits. In January 2018, the

month after President Donald Trump signed the tax

bill into law, the tech behemoth and third-largest

American company

said it would pay the new, lower tax and start

bringing the cash home. Just four months later,

Apple

said it would buy back $100 billion of its stock

and hike its dividend by 16 percent. Apple shares

increased almost 9 percent by the week’s end. In

April 2019, Apple

announced $75 billion more in buybacks, a move

analysts said would likely drive its stock price

higher. A day after the announcement, shares

increased in value nearly 5 percent. The stock

continued to hit record highs late last year.

That increase and higher dividends

augmented the holdings of 43 Republicans who voted

for the tax bill, including seven senators and their

spouses who owned Apple stock in 2018: John Hoeven

of North Dakota; David Perdue of Georgia; Arizona’s

Jeff Flake, now retired; Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma; and

the spouses of Pat Roberts of Kansas, Maine’s Susan

Collins, and Shelley Capito of West Virginia. A

spokesperson for Hoeven said that he “follows Senate

regulations and reporting requirements.” Sen.

Collins’s husband’s portfolio decisions are all made

by a financial adviser, a Collins spokesperson said,

and he has not bought or sold Apple stock since

2015.

Perdue is one of the wealthiest

senators, with a net worth of $15.8 million, $14

million of which is in stocks,

according to Roll Call. In 2018, with his wife,

Perdue owned $100,000 to $250,000 in Apple stock, he

reported. The couple sold some of it and received

annual dividends and capital gains that year between

$15,000 and $50,000.

The optics that the tax cuts would

boost the prices of stock he owned apparently didn’t

concern Perdue. Weeks before Republicans passed the

tax bill, Fox News host

Maria Bartiromo asked Perdue if he was worried

that the corporate cuts would result in buybacks and

increased dividends instead of new jobs. “Well,

Maria,” he answered, “I come from the school that,

you know, all of the above is acceptable. This is

capitalism.” He later added that it was all about

“capital flow,” whether for jobs, economic growth,

or dividends.

An affinity for

“small business” — and pass-throughs

Passing a law that helped fuel

increases in stock prices wasn’t the only way

Republicans enriched themselves. The new law also

contained a 20 percent deduction for income from

so-called “pass-through” businesses, a provision

called the “crown

jewel” of the act by the National Federation of

Independent Businesses, a lobbying group.

Pass-throughs are single-owner

businesses, partnerships, limited liability

companies, (known as LLCs) and special corporations

called S-corps. Most real estate companies are

organized as LLCs. Trump owns hundreds of them, and

the Center for Public Integrity’s analysis found

that 22 of the 47 members of the House and Senate

tax-writing committees in 2017 were invested in

them.

Pass-throughs can be found in any

industry. They pay no corporate taxes and steer

their profits as income to business owners or

investors, who are taxed only once at their

individual rates. Despite their favored treatment as

a business vehicle, the 2017 tax act did them

another favor: It allowed 20 percent to be deducted

off the top of the pass-through income for tax

purposes.

In the Senate, the champion for the

pass-through break was Ron Johnson, a Wisconsin

Republican who was a Budget Committee member when

the tax bill was being written. He argued that

because the bill was slated to give

big corporations a 14 percent cut in their tax rate,

smaller businesses should get a break, too. “I just

have in my heart a real affinity for these

owner-operated pass-throughs,” he

told the New York Times when the Senate was

considering the tax bill in November 2017.

No doubt Johnson, with his wife, held

interests that year in four real estate or

manufacturing LLCs worth between $6.2 million and

$30.5 million, from which they received income that

year between $250,000 and $2.1 million, according to

his financial disclosure form.

How much money lawmakers will pocket

from the 20 percent pass-through deduction can’t be

determined without an examination of their tax

returns. There are limits on how much of the

deduction can be taken based on total income and

business category. But in some cases, the tax

savings could run into the tens of thousands of

dollars. Johnson declined to comment for this

article.

And while the provision did help

small businesses in certain favored categories, the

benefits of the pass-through deduction are heavily

tilted toward the wealthy. Sixty-one percent of the

benefits of this provision will go to the top 1

percent of taxpayers in 2024, according to the Joint

Committee on Taxation, the congressional agency that

analyzes tax bills.

GOP real estate

owners make out big

Besides the law’s benefits to real

estate pass-throughs, real estate in general was

hugely favored by the tax law, allowing property

exchanges to avoid taxation, the deduction of new

capital expenses in just one year versus longer

depreciation schedules, and an exemption from limits

on interest deductions.

“If you are a real estate developer,

you never pay tax,” said Ed Kleinbard, a former head

of Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation.

Members of Congress own a lot of real

estate. Public Integrity’s review of financial

disclosures found that 29 of the 47 GOP members of

the committees responsible for the tax bill hold

interests in real estate, including small rental

businesses, LLCs, and massive real estate investment

trusts (REITs), which pay dividends to investors.

The tax bill allows REIT investors to deduct 20

percent from their dividends for tax purposes.

Real estate pass-throughs got an

especially sweet gift in the form of a provision

inserted into the tax bill behind the closed doors

of the House-Senate conference committee. The Senate

bill under consideration based a company’s

pass-through deductions on the total amount of wages

paid to employees. Because real-estate pass-through

companies typically have few employees, however,

this meant they could offer only tiny deductions to

investors.

A stroke of the pen fixed that:

Someone changed the law to allow

real estate companies to use the value of their

assets — in addition to the size of their payrolls —

to calculate pass-through benefits. Because such

companies can hold sizable assets, suddenly they,

too, could offer the full 20 percent deduction to

investors.

“In my judgment, it was a big

giveaway to the real estate community, and they are

very good lobbyists,” said Steve Rosenthal, a senior

fellow at the nonpartisan Urban-Brookings Tax Policy

Center in Washington, DC. That giveaway contributed

to last year’s record $1.02 trillion federal revenue

shortfall.

One Republican senator who benefited

from the last-minute provision was Tennessee’s Bob

Corker, who at the time owned or was a partner in 18

real estate businesses, LLCs, and partnerships,

records show. His reported income from them was

between $2.1 million and $11.1 million in 2017.

Corker, who retired in 2018, told Public Integrity

he had nothing to do with the provision or the 20

percent pass-through deduction. It was all Ron

Johnson’s idea, Corker said.

“The budget deficit is going up so

that people like Ron Johnson and Bob Corker can pay

less in taxes,” said Hauser, of the Revolving Door

Project.

Forbidding

self-dealing would help close the loopholes

Republicans wouldn’t have had many of

these apparent conflicts if Elizabeth Warren’s

anti-corruption plan had been in effect.

Much of the plan was pulled from her

Anti-Corruption and Public Integrity Act, which

she introduced in the Senate in 2018. Among its

provisions, the bill would forbid lawmakers to own

or trade individual stocks, bonds, commodities,

hedge funds, derivatives, or “complex investment

vehicles.” Members would be required to put their

assets in “widely held investment vehicles” such as

mutual funds. Warren and her husband were invested

in 20 mutual funds in 2017, but no individual

stocks.

Members could no longer own

commercial real estate, though they could keep

businesses with revenue under $5 million — which

could include a lot of pass-throughs. Warren’s bill

hasn’t moved out of the Senate Finance Committee; an

identical bill in the House also remains idle.

Warren’s plan faces an uphill climb,

even among Democrats. “It’s very difficult to get

congresspeople to pass rules that make life

exceedingly difficult for themselves,” said Beth

Rotman, the money in politics and ethics director at

Common Cause, a government watchdog in Washington,

DC.

But it’s happened in the past. In

1978, Congress passed the

Ethics in Government Act in the wake of the

Watergate scandal. It requires certain government

officials, including members of Congress, to file

annual financial forms — records the Center for

Public Integrity used for this analysis. And in

2012, Congress passed a

bill that made it unlawful to use insider

information to trade stocks, required members to

report stock trades within 45 days of the

transaction, and required lawmakers to file

disclosure forms online in a searchable, sortable,

and downloadable database —

so conflicts of interest would be easy to

detect. (Within a year, Congress had removed the

“searchable and sortable” language from the law. The

financial disclosures are now available online, but

they are not easily searched or sorted.)

Apparently just because of

disclosure, stock trading by senators dropped by

about two-thirds in the three years following the

law’s enactment,

according to a study by Craig Holman at the

government watchdog group Public Citizen. But Holman

said he found that some senators continued to trade

in stocks in the very businesses they oversaw in

their committees — a practice Public Citizen wants

banned.

Ironically, it was Congress that

passed laws that restrict other federal government

officials from owning stocks or assets that would

benefit from the officials’ decisions — or require

them to recuse themselves from such decisions. Yet

Congress has not passed legislation that bans itself

from the same practice. “Congress should have the

same rules put on them that the executive branch

has,” said Rotman of Common Cause. “The executive

branch conflict of interest rules are stronger.”

For the 2017 tax act, Holman of

Public Citizen notes that about six years ago,

researchers found that more than half of the members

of Congress were millionaires. “They are passing tax

laws and legislation that disproportionately favors

the wealthy class,” Holman said. “And that means

they personally benefit from this type of

legislation.

“And, from what we’ve seen,

especially from the tax cuts and jobs act of 2017,”

he added, “that tax bill clearly favored the very

wealthy over the rest of Americans. And that means

it favored Congress over the rest of America.”

Peter Cary is a consulting

reporter for the Center for Public Integrity, a

nonprofit investigative news organization in

Washington, DC.

Do you agree or disagree? Post

your comment here

==See Also==