The Centrist Delusion: ‘Middle Ground’

Politics Aren’t Moderate, They’re

Dangerous

By

Raoul Martinez

December 12, 2019 "Information

Clearing House"

-

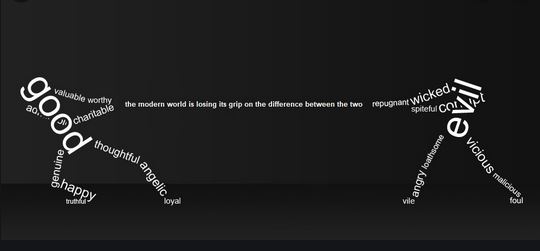

In

a world of competing narratives serving

competing interests, there’s always a

temptation to gravitate to the political

centre ground, the would-be midpoint

between two apparent extremes, with its

aura of moderation, reasonableness and

realism. After all, isn’t the truth

supposed to be ‘somewhere in the

middle’, a composite of competing

claims? The simple answer is no. Not in

science and not in politics. When there

are two opposing sides to a debate,

sometimes the midway position is

empirically false or morally abhorrent.

In every civilisation, the centre ground

of political opinion has been home to

dangerous, inaccurate and oppressive

ideas.

A consensus of the

powerful.

In

eighteenth century Britain, centrists

endorsed slavery, reformists called for

improved working conditions for slaves

and radicals demanded the abolition of

the entire institution. As historian

Adam Hochschild recounts, if in 1787

“you had stood on a London street corner

and insisted slavery was morally wrong

and should be stopped, nine out of ten

listeners would have laughed you off as

a crackpot. The tenth might have agreed

with you in principle, but assured you

ending slavery was wildly impractical.”

The centre ground is a social

construction, commanding most loyalty

from those whose privilege protects them

from the ravages of the system they

support.

The centre ground doesn’t necessarily

represent majority opinion — it’s a

consensus of the powerful. In the US,

for instance, public opinion has for

decades been in favour of universal

healthcare, while most US politicians —

Republicans and Democrats — have

staunchly opposed it. The shifting

centre ground has reframed political

perceptions to such an extent that

someone like Bernie Sanders, who would

once have been regarded as a

middle-of-the-road politician in the

mould of president Franklin D.

Roosevelt, has long been characterised

as a radical insurgent.

Struggles to abolish slavery, end child

labour, resist colonialism, extend

voting rights, achieve racial and gender

equality, and grant basic human rights

to all required courageous members of

society to challenge the dominant

identities and narratives of their day.

Those who did were labelled as

extremists, and sometimes punished with

imprisonment or death.

|

Are You Tired Of

The Lies And

Non-Stop Propaganda?

|

It’s easy to look back at the injustices

of history with moral clarity and ignore

the fact that this clarity owes its

existence to the hard work of those who

came before us. Our moral compass is the

outcome of yesterday’s sacrifices and

struggles.

Extremists for love

or hate?

Today, Martin Luther King is viewed by

many as one of the greatest Americans in

history. In a 2011 survey, 94 percent of

those polled viewed him positively, yet

in his own lifetime, a 1966 Gallup poll

found that 63 percent of respondents

viewed him negatively. In 1961, a Gallup

survey showed that even when Americans

supported the stated goals of the civil

rights movement, a majority did not

support their tactics — sit-ins, freedom

buses and mass demonstrations. When King

spoke out against the Vietnam war, Life

magazine described his speech as

“demagogic slander”. King, Rosa Parks

and other civil rights activists were

regularly called ‘Anti-American’,

‘communists’ and ‘traitors’. The FBI

referred to him as “the most dangerous

negro leader in this Nation”. Robert

Kennedy signed off on a surveillance

program to monitor King’s home, offices,

phones and hotel rooms, as well as those

of his colleagues. At one point, the FBI

even sent him an unsigned letter

encouraging him to kill himself. Why?

King was deeply critical of the centrist

politics of the day. His demands for

change challenged the legal, cultural

and political mainstream. In his famous

Letter From Birmingham Jail, he

described his views of the sympathetic

so-called moderate:

“I have almost reached the

regrettable conclusion that the

Negro’s great stumbling block in his

stride toward freedom is not the

White Citizen’s Council-er or the Ku

Klux Klanner, but the white

moderate, who is more devoted to

“order” than to justice; who prefers

a negative peace which is the

absence of tension to a positive

peace which is the presence of

justice; who constantly says: “I

agree with you in the goal you seek,

but I cannot agree with your methods

of direct action”; who

paternalistically believes he can

set the timetable for another man’s

freedom; who lives by a mythical

concept of time and who constantly

advises the Negro to wait for a

“more convenient season.” Shallow

understanding from people of good

will is more frustrating than

absolute misunderstanding from

people of ill will. Lukewarm

acceptance is much more bewildering

than outright rejection.”

King was often called an extremist.

Initially he was distressed by the term

but later “gained a measure of

satisfaction from the label”. As he put

it, “the question is not whether we will

be extremists, but what kind of

extremists we will be. Will we be

extremists for hate or for love? Will we

be extremists for the preservation of

injustice or for the extension of

justice?”. King felt that the world

desperately needed creative extremists

for “love, truth and goodness” and

argued that freedom was never given away

by systems of power. It always had to be

won by “strong, persistent and

determined action”.

One of the reasons King is celebrated

now is that his legacy has been

sanitised in ways that distort what he

believed and fought for. He is

remembered for his inspiring message of

racial equality, an area where the

dominant story has been revised, but his

message of economic justice and his

anti-war campaigning are deemphasised or

ignored. Few people associate him with

the view that the global system of

capitalism takes “necessities from the

masses to give luxuries to the classes”

and has “outlived its usefulness”. These

views are as challenging today as they

were in King’s time.

The saintly aura of bygone human rights

icons is rarely matched by those who

wage the same struggles today. They are

constructed after a battle has been won,

and in ways that prevent us learning

from history. How many of us would have

supported King and the movement he

represented when to do so came at a

cost, when the struggle was dangerous,

the methods unpopular, and when those

who did support him were dismissed as

cultists or threats to national

security?

It

takes courage, effort, and imagination

to rewrite dominant narratives, to

perceive the familiar as extreme and the

normal as outrageous. It takes robust

understanding to develop and defend

convictions that are incompatible with

the assumptions of peers and the

powerful. This is the moral challenge of

every generation: to see beyond the

prejudices, lies and smears of their own

time; to identify the injustices,

threats and problems of their era, and

work together to overcome them. The

location of the centre ground is never a

given — it is precisely what we want to

change when we engage in political

struggle.

The unconvincing mask

of moderation.

In

my own lifetime, centre ground

politicians have launched illegal wars

based on false claims, in which hundreds

of thousands of innocent people were

killed; made billions in profits from

selling arms to the most repressive

regimes on the planet; systematically

dismantled the regulations of the

financial sector leading to one of the

most devastating economic crashes in

history; pursued, unnecessarily,

economic austerity which has resulted in

the deaths of hundreds of thousands of

people and inflicted great suffering on

millions more; allowed tens of thousands

of desperate souls to drown in the

Mediterranean; and all while overseeing

soaring inequality within and between

nations. These are serious and tragic

failings, but the problems with

business-as-usual politics go deeper

still. If we take the warnings of the

scientific community seriously — and we

must — the very survival of our

civilisation depends on us radically and

urgently redefining the centre ground of

political opinion.

Confronted

with the extremism of the far right,

many in the establishment are clamouring

for a return to the centre-ground, to

turn back the clock to the 1990s. These

dynamics played out clearly in the US

election of 2016. During the Democratic

primaries,

poll after poll

showed that Bernie Sanders, with his

populist progressivism, stood a far

better chance of beating Donald Trump

than Hillary Clinton. The data signalled

that a contest between Trump and Clinton

would be extremely close, with some

polls putting Trump ahead of Hillary,

but that a contest between Trump and

Sanders would very much favour Sanders.

In May 2016,

analytics expert Dustin Woodard wrote

that Sanders “beats Trump in every

single poll and by an average margin of

14.1 percent.” Yet institutional support

— within the Democratic party itself,

but also in the wider media — rallied

behind Clinton. According to Democratic

National Committee Chair, Donna Brazile,

this support extended to rigging the

primaries to keep Sanders out. At a time

of deep anti-establishment sentiment,

this was a gift to Trump. Ultimately,

Clinton won the popular vote but lost

the election. A poll on the eve of the

election suggested that Sanders would

have emerged with a large majority.

After the election, pollster guru Nate

Silver concluded “Bernie probably would

have won”.

Clinton’s

loss is symptomatic of something deeper:

an establishment committed to holding

the unconvincing mask of moderation

firmly in place over a corrupt,

exploitative and unsustainable system.

Trump and the emboldened far right

across Europe represent a new category

of threat, but the reality behind this

mask reveals greater continuity between

Trump and previous administrations than

we have been led to believe. Trump’s

rhetoric about immigrants is hateful,

but

Obama deported more immigrants

than all of the presidents in the

twentieth century combined. Trump’s idea

to build a wall along the Mexico border

has rightly angered many, but in effect

the wall already exists, consisting of

an extensive system of detection

technologies, guards, and hundreds of

miles of barriers and fences.

Moreover,

under Obama, the annual budget for

border and immigration enforcement rose

to $5bn more than all other federal law

enforcement agencies combined. Trump’s

brash climate denial is terrifying, but

Obama’s environmental record was dismal.

According to climate scientist James

Hansen,

he “failed miserably”

on climate change, presiding over

policies that were “late, ineffectual

and partisan”. Indeed, under Obama’s

watch, the US became the world’s number

one producer of fossil fuels; oil, gas,

and coal subsidies rose by 45 percent

(to almost $20 billion a year); and the

US repeatedly weakened climate

negotiations, resisting any legally

binding emission targets. The assessment

of

Harvard professor Cornell West

is that: “Despite some progressive words

and symbolic gestures, Obama chose to

ignore Wall Street crimes, reject

bailouts for homeowners, oversee growing

inequality and facilitate war crimes

like US drones killing innocent

civilians abroad.”

Redefining the centre

ground.

The centrism of our time

is the gateway drug to the far right.

This lesson needs to be learned — and

quickly. Just as the US establishment

treated Sanders as a greater threat than

Trump, the UK establishment — even its

more progressive wing — has treated

Jeremy Corbyn as a greater threat than

Boris Johnson. As a result, during the

present UK general election campaign, I

have heard friends warn of the dangers

of

all

extremes: both Corbyn on the left and

Johnson on the right. I have seen the

Liberal Democrats attempting to position

themselves as the sensible choice

between these wild alternatives. A

string of prominent voices, from Tony

Blair to John Major, have called for a

return to the centre ground. They, and

many others, suffer from

the

centrist delusion:

the notion that the existing

centre-ground, almost by definition, is

the home of reasonableness and

moderation. It’s intellectually lazy,

oblivious to the fact that it has been

the establishment consensus — embodied

by the likes of Tony Blair and Barack

Obama — that has created the

intersecting inequality, democratic and

climate crises we now face. Failure to

recognise the disease of toxic centrism

prevents us treating its ugly symptoms:

Trump, Bolsonaro, Netanyahu,

Modi and now Johnson. Ideologies of hate

are thriving on the failure of

establishment politics to respond to the

crises it has unleashed.

In

the UK’s imminent election, the choices

are clear. The Conservative manifesto

was described by Paul Johnson of the

Institute

for Fiscal Studies

as being so lacking in substance that it

would be inadequate for a budget, let

alone a full term in government. And the

promises that have been made (such as

50,000 new nurses and 40 new hospitals)

have not survived scrutiny. But we don’t

need a manifesto to know what we are

going to get. A party funded by

billionaires and shielded by the

billionaire-owned press does not exist

to serve the majority. The Tories have

been in power for almost a decade, with

Johnson offering them firm support

throughout most of that time. Judging by

their record, we can expect more NHS

privatisation, more tax cuts for the

rich, more inequality, more

homelessness, more public and private

debt, more hungry children, more

underfunded schools, more weapons sold

to human-rights-abusing regimes, more

scapegoating, and more broken promises.

And in the context of the climate crisis

— the most serious issue we face — their

manifesto, should it be emulated,

amounts to a death sentence for

countless people in the Global South and

a grim future for us all.

Internationally, a Johnson government

constitutes a boost to the far right

which has been chalking up victories

from the US to Brazil to Hungary.

The Liberal Democrats embody the toxic

centre ground. Their 2045

decarbonisation target is a polite form

of climate denial — inadequate to the

extreme. Their leader, Jo Swinson, has

voted with the Tories over 800 times,

more than a number of Tory politicians.

These votes include supporting fracking

and backing a punishing austerity regime

which not only was economically

illiterate,

costing

Britain over £100 billion,

but is implicated in the deaths of over

120,000

Britons.

One of the researchers behind this

finding called it a form of ‘economic

murder’. Shortly before the election,

the Liberal Democrats abstained on a

motion demonstrating opposition to NHS

privatisation. Since the start of the

campaign, they have repeatedly misled

the electorate about how to vote

tactically to keep out the Tories. By

splitting the vote, they may well hand

the keys of No. 10 to Johnson,

guaranteeing a disastrous Brexit, and

contravening their stated aim for the

election. Perhaps most tellingly, from

Gordon Brown to Ed Miliband to Corbyn

they have shown a far greater

willingness to work with the

Conservatives than Labour.

A new common sense.

The Labour manifesto, in stark contrast,

is a big step towards a genuinely

reasonable and rational centre ground —

a new common sense. Placed in

international context, their spending

and taxation plans, endorsed by hundreds

of senior economists, are unremarkable.

Were every spending pledge implemented,

the UK would still be spending less than

Sweden, Norway, Belgium, Finland and

France. Were corporation tax raised to

26%, as Labour intend, it would still be

lower than in Germany, France,

Australia, Canada and Japan. It may not

be radical according to international

standards but, in the context of British

politics, it represents a warm embrace —

a decisive break with neoliberalism that

reverses austerity, renationalises the

NHS, rescues our schools, removes the

debt burden from our students and makes

affordable housing a reality. When it

comes to addressing the climate crisis,

Labour would turn the UK into a world

leader while creating a million green

jobs in the process. More needs to be

done, but it’s a bold start — one judged

by Friends of the Earth to make them

greener than even the Greens. Labour’s

Brexit position — a referendum within

six months with a credible Leave option

beside a Remain option — is the height

of moderation in a nation split down the

middle by the issue.

If

the majority of people simply voted in

their own interests, Labour would come

close to winning almost every seat in

parliament on December 12. Yet the

billionaire-owned British media — parked

as it is on a socially and ecologically

toxic centre ground — has made the

choice between a warm embrace and punch

in the face seem confusing and

difficult. How have they achieved this?

Mainly by moving the conversation away

from policies, voting records and party

funders, and onto the reputations of

party leaders. It’s easy to destroy

someone’s reputation, much harder to

destroy support for the NHS, affordable

housing, well-funded schools and a

million green jobs.

Since his election as leader, Corbyn has

been attacked for being incompetent, a

threat to national security,

disrespectful to the queen, a terrorist

sympathiser, a foreign spy, a Russian

stooge and, most recently, an

antisemite. From within his own party, a

small but determined group of MPs and

officials have been working to force him

out, orchestrating mass resignations

from the shadow cabinet, public warnings

of electoral disaster, repeated pleas

for him to resign, a failed leadership

challenge, and numerous attempts to

smear his reputation and undermine his

credibility. Those behind these attacks

have demonstrated a willingness to

sabotage the electoral chances of their

own party in order to achieve this aim.

This is nothing new. It is worth

remembering that socialist Tony Benn,

who passed away at the age of 88 having

achieved near national treasure status,

was — when running for deputy leader of

the Labour party — viciously attacked by

the media and labelled “the most

dangerous man in Britain”. He was

demonised in news articles and cartoons,

repeatedly called “mad”, a “loony

leftist”, and once was depicted as

Hitler in a Daily Express cartoon. Like

Corbyn, he was attacked by other Labour

MPs such as Tony Crosland who described

him as “just a bit cracked”. The media

attacks reached their highest intensity

when Benn ran for the deputy leadership.

David Powell, the author of Benn’s

biography, described the ensuing

campaign as “venomous”. According to

Labour MP and Benn supporter, Michael

Meacher, ‘There was never less than a

half-page of vitriol in the press every

day, and the source was the right wing

of the Labour party.” When Benn stood in

a by-election in 1983, the day of

polling saw the Sun run a feature with

the headline: “Benn on the couch: a top

psychiatrist’s view of Britain’s leading

leftie”. The article diagnosed Benn as

“a Messiah figure hiding behind the mask

of the common man … greedy for power and

willing to do anything to get it.” Benn

himself concluded that press owners used

their papers “to campaign

single-mindedly in defence of their

commercial interests and the political

policies which will protect them.”

Protecting privilege.

Those holding most of the wealth and

power in society need centrist politics

to rationalise and protect their extreme

privilege. They work to normalise

whatever policies and ideas will favour

them. Over the last few decades, this

has meant low taxation, deregulation and

privatisation — neoliberalism — coupled

with an amoral, exploitative and

extractivist foreign policy justified

under the rubric of ‘national interest’.

To succeed, a compliant media is

essential. It is absurd to call the

media ‘free’ when it is controlled by a

handful of billionaires whose outlets

each day feed millions of people words

and images designed to reproduce the

toxic centre ground from which they

profit. Historian Mark Curtis recently

conducted a search of the UK national

press spanning the three months leading

up to the election. He found 1450

articles on “Corbyn and antisemitism”

and only 164 covering “Johnson and

Islamophobia”. He also found 272 pieces

on “Corbyn and the IRA” compared with

only 2 mentioning “Johnson, Yemen and

war crimes”.

In

some parts of the world, individuals and

groups that threaten entrenched

interests are assassinated. In Britain,

they are character assassinated. When

you are swindling most of the people,

most of the time, the only way to

engineer consent is through deception.

This is a constant, yet the current Tory

campaign has reached Trumpian

proportions of deceit. To give just one

example, the Coalition for Reform in

Political Advertising, a non-partisan

group, have found that 88 percent of the

Conservative party’s promoted ads, on

Facebook and elsewhere, contain false

claims. Hundreds of the ads put out by

the Liberal Democrats were found to be

potentially misleading. As for Labour,

not a single ad was found to contain

falsehoods or distortions.

We

have long been told that there’s no

smoke without fire. Unfortunately, in

the world of politics, not only is there

smoke without fire, there is often fire

without smoke. Real crises go unnoticed

while fictional crises saturate the news

cycle. This pattern has brought our

civilisation to a crossroads. The scale

of the crises faced in Britain and the

world requires a rapid, bold, ambitious

change of direction. Winning this change

requires sustained struggle each and

every day. But some days are of special

significance, presenting opportunities

to dramatically broaden or narrow our

collective horizons. December 12, 2019

is one of those days. Let’s use it to

start this change. Let’s elect a Labour

government.

Raoul Martinez is a philosopher and the

author of Creating Freedom: Power,

Control and the Fight for our Future.