The Road to Damascus: How the Syria War was Won

By Pepe Escobar

October 18, 2019 "Information Clearing House" - What is happening in Syria, following yet another Russia-brokered deal, is a massive geopolitical game-changer. I’ve tried to summarize it in a single paragraph this way:

“It’s a quadruple win. The U.S. performs a face saving withdrawal, which Trump can sell as avoiding a conflict with NATO ally Turkey. Turkey has the guarantee – by the Russians – that the Syrian Army will be in control of the Turkish-Syrian border. Russia prevents a war escalation and keeps the Russia-Iran-Turkey peace process alive. And Syria will eventually regain control of the entire northeast.”

Syria may be the biggest defeat for the CIA since Vietnam.

Yet that hardly begins to tell the whole story.

Allow me to briefly sketch in broad historical strokes how we got here

It began with an intuition I felt last month at the tri-border point of Lebanon, Syria and Occupied Palestine; followed by a subsequent series of conversations in Beirut with first-class Lebanese, Syrian, Iranian, Russian, French and Italian analysts; all resting on my travels in Syria since the 1990s; with a mix of selected bibliography in French available at Antoine’s in Beirut thrown in.

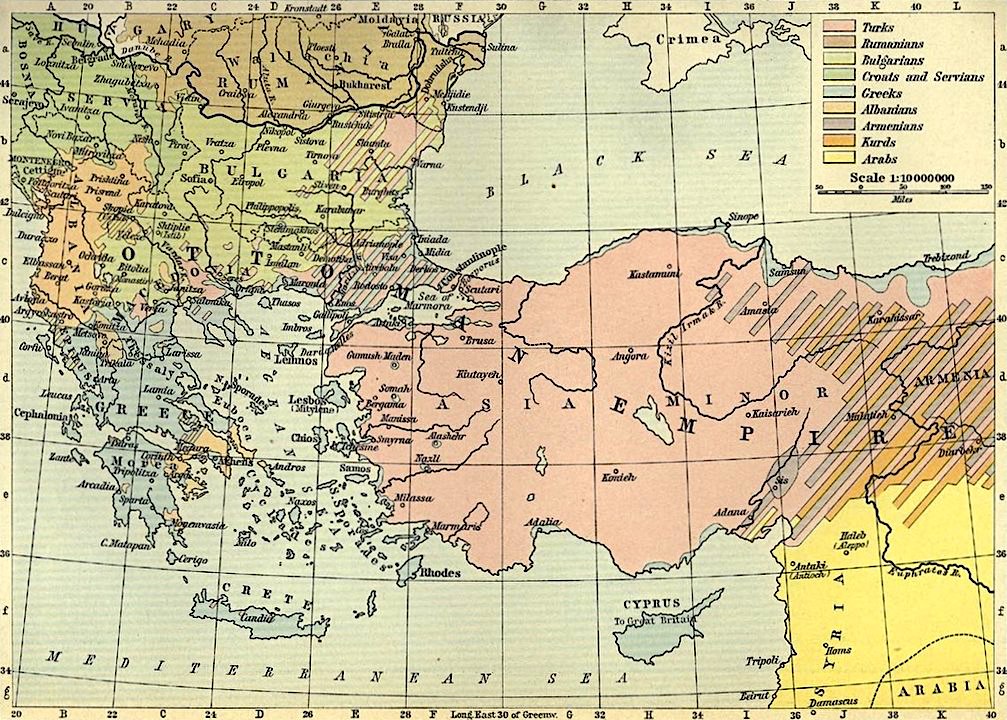

The Vilayets

Let’s start in the 19thcentury when Syria consisted of six vilayets — Ottoman provinces — without counting Mount Lebanon, which had a special status since 1861 to the benefit of Maronite Christians and Jerusalem, which was a sanjak (administrative division) of Istanbul.

The vilayets did not define the extremely complex Syrian identity: for instance, Armenians were the majority in the vilayet of Maras, Kurds in Diyarbakir – both now part of Turkey in southern Anatolia – and the vilayets of Aleppo and Damascus were both Sunni Arab.

Nineteenth century Ottoman Syria was the epitome of cosmopolitanism. There were no interior borders or walls. Everything was inter-dependent.

Then the Europeans, profiting from World War I, intervened. France got the Syrian-Lebanese littoral, and later the vilayets of Maras and Mosul (today in Iraq). Palestine was separated from Cham (the “Levant”), to be internationalized. The vilayet of Damascus was cut in half: France got the north, the Brits got the south. Separation between Syria and the mostly Christian Lebanese lands came later.

There was always the complex question of the Syria-Iraq border. Since antiquity, the Euphrates acted as a barrier, for instance between the Cham of the Umayyads and their fierce competitors on the other side of the river, the Mesopotamian Abbasids.

James Barr, in his splendid “A Line in the Sand,” notes, correctly, that the Sykes-Picot agreement imposed on the Middle East the European conception of territory: their “line in the sand” codified a delimited separation between nation-states. The problem is, there were no nation-states in region in the early 20thcentury.

The birth of Syria as we know it was a work in progress, involving the Europeans, the Hashemite dynasty, nationalist Syrians invested in building a Greater Syria including Lebanon, and the Maronites of Mount Lebanon. An important factor is that few in the region lamented losing dependence on Hashemite Medina, and except the Turks, the loss of the vilayet of Mosul in what became Iraq after World War I.

In 1925, Sunnis became the de facto prominent power in Syria, as the French unified Aleppo and Damascus. During the 1920s France also established the borders of eastern Syria. And the Treaty of Lausanne, in 1923, forced the Turks to give up all Ottoman holdings but didn’t keep them out of the game.

The Turks soon started to encroach on the French mandate, and began blocking the dream of Kurdish autonomy. France in the end gave in: the Turkish-Syrian border would parallel the route of the fabled Bagdadbahn — the Berlin-Baghdad railway.

In the 1930s France gave in even more: the sanjak of Alexandretta (today’s Iskenderun, in Hatay province, Turkey), was finally annexed by Turkey in 1939 when only 40 percent of the population was Turkish.

The annexation led to the exile of tens of thousands of Armenians. It was a tremendous blow for Syrian nationalists. And it was a disaster for Aleppo, which lost its corridor to the Eastern Mediterranean.

To the eastern steppes, Syria was all about Bedouin tribes. To the north, it was all about the Turkish-Kurdish clash. And to the south, the border was a mirage in the desert, only drawn with the advent of Transjordan. Only the western front, with Lebanon, was established, and consolidated after WWII.

This emergent Syria — out of conflicting Turkish, French, British and myriad local interests —obviously could not, and did not, please any community. Still, the heart of the nation configured what was described as “useful Syria.” No less than 60 percent of the nation was — and remains — practically void. Yet, geopolitically, that translates into “strategic depth” — the heart of the matter in the current war.

From Hafez to Bashar

Starting in 1963, the Baath party, secular and nationalist, took over Syria, finally consolidating its power in 1970 with Hafez al-Assad, who instead of just relying on his Alawite minority, built a humongous, hyper-centralized state machinery mixed with a police state. The key actors who refused to play the game were the Muslim Brotherhood, all the way to being massacred during the hardcore 1982 Hama repression.

Secularism and a police state: that’s how the fragile Syrian mosaic was preserved. But already in the 1970s major fractures were emerging: between major cities and a very poor periphery; between the “useful” west and the Bedouin east; between Arabs and Kurds. But the urban elites never repudiated the iron will of Damascus: cronyism, after all, was quite profitable.

Damascus interfered heavily with the Lebanese civil war since 1976 at the invitation of the Arab League as a “peacekeeping force.” In Hafez al-Assad’s logic, stressing the Arab identity of Lebanon was essential to recover Greater Syria. But Syrian control over Lebanon started to unravel in 2005, after the murder of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, very close to Saudi Arabia, the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) eventually left.

Bashar al-Assad had taken power in 2000. Unlike his father, he bet on the Alawites to run the state machinery, preventing the possibility of a coup but completely alienating himself from the poor, Syrian on the street.

What the West defined as the Arab Spring, began in Syria in March 2011; it was a revolt against the Alawites as much as a revolt against Damascus. Totally instrumentalized by the foreign interests, the revolt sprang up in extremely poor, dejected Sunni peripheries: Deraa in the south, the deserted east, and the suburbs of Damascus and Aleppo.

|

Are You Tired Of The Lies And Non-Stop Propaganda? |