You Are

Not In Control

By

Dmitry Orlov

February 16, 2017 "Information

Clearing House"

- "Dmitry

Orlov"

- My recent book tour was very valuable,

among other things, in gauging audience response

to the various topics related to the

technosphere and its control over us.

Specifically, what seems to be generally missing

is an understanding that the technosphere

doesn’t just control technology; it controls our

minds as well. The technosphere doesn’t just

prevent us from choosing technologies that we

think may be appropriate and rejecting the ones

that aren’t. It controls our tastes, making us

prefer things that it prefers for its own

reasons. It also controls our values, aligning

them with its own. And it controls our bodies,

causing us to treat ourselves as if we were

mechanisms rather than symbiotic communities of

living cells (human and otherwise).

None of this invalidates the approach I proposed

for shrinking the technosphere which is based on

a harm/benefit analysis and allows us to ratchet

down our technology choices by always picking

technologies with the least harm and the

greatest benefit. But this approach only works

if the analysis is informed by our own tastes,

not the tastes imposed on us by the technosphere,

by our values, not the technosphere’s values,

and by our rejection of a mechanistic conception

of our selves. These choices are implicit in the

32 criteria used in harm/benefit analysis,

favoring local over global, group interests over

individual interests, artisanal over industrial

and so on. But I think it would be helpful to

make these choices explicit, by working through

an example of each of the three types of control

listed above. This week I'll tackle the first of

these.

A good example of how the technosphere controls

our tastes is the personal automobile. Many

people regard it as a symbol of freedom and see

their car as an extension of their

personalities. The freedom to be car-free is not

generally regarded as important, while the

freedoms bestowed by car ownership are rather

questionable. It is the freedom to make car

payments, pay for repairs, insurance, parking,

towing and gasoline. It is the freedom to pay

tolls, traffic tickets, title fees and excise

taxes. It is the freedom to spend countless

hours stuck in traffic jams and to suffer

injuries in car accidents. It is the freedom to

bring up neurologically damaged children by

subjecting them to unsafe carbon monoxide levels

(you are encouraged to have a CO detector in

your house, but not in your car—because it would

be going off all the time). It is the freedom to

suffer indignities when pulled over by police,

especially if you’ve been drinking. In terms of

a harm/benefit analysis, private car ownership

makes no sense at all.

It is often argued that a car is a necessity,

although the facts tell a different story.

Worldwide, there are 1.2 billion vehicles on the

road. The population of the planet is over 7

billion. Therefore, there are at least 5.8

billion people alive in the world who don’t own

a car. How can something be considered a

necessity if 82% of us don’t seem to need it? In

fact, owning a car becomes necessary only in a

certain specific set of circumstances. Here are

some of the key ingredients: a landscape that is

impassable except by motor vehicle, single-use

zoning that segregates land by residential,

commercial, agricultural and industrial uses, a

lifestyle that requires a daily commute, and a

deficit of public transportation. In turn,

widespread private car ownership is what enables

these key ingredients: without it, situations in

which private car ownership becomes a necessity

simply would not arise.

Now, moving people about the landscape is not a

productive activity: it is a waste of time and

energy. If you can live, send your children to

school, shop and work all without leaving the

confines of a small neighborhood, you are bound

to be more efficient than someone who has to

drive between these four locations on a daily

basis. But the technosphere is rational to a

fault and is all about achieving efficiencies.

And so, an obvious question to ask is, What is

it about the car-dependent living arrangement,

and the landscape it enables, that the

technosphere finds to be efficient? The

surprising answer is that the technosphere

strives to optimize the burning of gasoline;

everything else is just a byproduct of this

optimization.

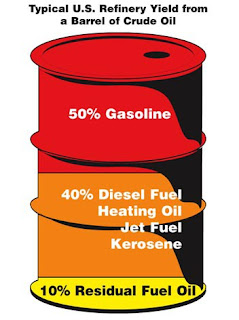

It turns

out that the fact that so many people are forced

to own a car has nothing to do with

transportation and everything to do with

petroleum chemistry. About half of what can be

usefully extracted from a barrel of crude oil is

in the form of gasoline. It is possible to boost

the fraction of other, more useful products,

such as kerosene, diesel fuel, jet fuel and

heating oil, but not by much and at a cost of

reduced net energy. But gasoline is not very

useful at all. It is volatile (quite a lot of it

evaporates, especially in the summer); it is

chemically unstable and doesn’t keep for long;

it is toxic and carcinogenic. It has a rather

low flash point, limiting the compression ratio

that can be achieved by gasoline-fueled engines,

making them thermodynamically less efficient. It

is useless for large engines, and is basically a

small-engine fuel. Gasoline-powered engines

don’t last very long because gasoline-air

mixture is detonated (using an electric spark)

rather than burned, and the shock waves from the

detonations cause components to wear out

quickly. They have few industrial uses; all of

the serious transportation infrastructure,

including locomotives, ships, jet aircraft,

tractor-trailers, construction equipment and

electrical generators run on petroleum

distillates such as kerosene, jet fuel, diesel

oil and bunker fuel.

If it weren’t for widespread private car

ownership, gasoline would have to be flared off

at refineries, at a loss. In turn, the cost of

petroleum distillates—which are all of the

industrial fuels—would double, and this would

curtail the technosphere’s global expansion by

making long-distance freight much more

expensive. The technosphere’s goal, then, is to

make us pay for the gasoline by forcing us to

drive. To this end, the landscape is structured

in a way that makes driving necessary. The fact

that to get from a Motel 8 on one side of the

road to the McDonalds on the other requires you

to drive two miles, navigate a cloverleaf, and

drive two miles back is not a bug; it's a

feature. When James Kunstler calls suburban

sprawl “the greatest misallocation of resources

in human history” he is only partly right. It is

also the greatest optimization in exploiting

every part of the crude oil barrel in the

history of the technosphere.

The proliferation of small gasoline-burning

engines in the form of cars enables another

optimization, forcing us to pay for another

generally useless fraction of the crude oil

barrel: road tar. Lots of cars require lots of

paved roadways and parking lots. Thus, the

technosphere wins twice, first by making us pay

for the privilege of disposing of what is

essentially toxic waste at our own risk and

expense, then by making us pay for spreading

another form of toxic waste all over the ground.

Suburban sprawl is not a failure of urban

planning; it is a success story in enslaving

humans and making them toil on behalf of the

technosphere while causing great damage to

themselves and to the environment. Needless to

say, you have absolutely no control over any of

this. You. Are. Not. In. Control. You can vote,

you can protest, you can lobby, donate to

environmentalist groups, attend conferences on

urban planning… and you would just be wasting

your time, because you can't change petroleum

chemistry.

That the need to make people buy gasoline trumps

all other considerations becomes obvious if we

observe how the technosphere reacts whenever

gasoline demand falters. When rampant wealth

inequality started making owning a car

unaffordable for more and more people, the

solution was to introduce larger cars for those

who could still afford one: minivans for the

mommies, pickup trucks for the daddies, and for

everyone the now common SUV. And now that

gasoline demand is dropping again because of

falling labor participation rate and an increase

in the number of people who telecommute, the

solution will no doubt be driverless cars which

will cruise around aimlessly burning gasoline.

Mommies may think that a minivan will keep their

kiddies safer than a compact would (not true

unless they have 8-9 kids). Daddies may think

that the pickup truck is a sign of manliness

(true if you are some sort of gofer/roustabout;

pickup trucks are driven by picker-uppers, a

subspecies of gofer/roustabout). But all they

are doing is obeying “The Third Law of the

Technosphere,” if you will: “For every

improvement in the efficiency of gasoline-fired

engines, there must be an equal and opposite

improvement in inefficiency.”

So,

perhaps you should just relax and go with the

flow. After all, being a slave in the service of

the technosphere is not immediately

life-threatening… unless you crash into a tree

or get run over by a drunk. But there is another

problem: this arrangement isn’t going to last.

The net energy that can be extracted out of a

barrel of oil is quickly shrinking. In less then

a decade the energy surplus required to maintain

a car-centric lifestyle will no longer exist. If

private car ownership and daily driving are

required of you in order to survive, then you

won’t survive. There goes at least 18% of the

world’s population, which will find itself

stranded in the middle of an impassable

landscape. Oops!

Given that you are not in control, and given

that the car-centric lifestyle is an

evolutionary dead end for your subspecies, what

can you do? The answer is obvious: you can plan

your escape, then join the other 82% of the

world’s population, which is able to live

car-free. Some of them even manage to live

entirely outside of the reach of the

technosphere. Let their example be your

inspiration.

The views expressed in this article are solely

those of the author and do not necessarily

reflect the opinions of Information Clearing

House.

|

Click for

Spanish,

German,

Dutch,

Danish,

French,

translation- Note-

Translation may take a

moment to load.

What's your response?

-

Scroll down to add / read comments

Please

read our

Comment Policy

before posting -

It is unacceptable to slander, smear or engage in personal attacks on authors of articles posted on ICH.

Those engaging in that behavior will be banned from the comment section.

|

| |

|